Blogs review: the comparative performance of fixed and flexible ER regimes

What’s at stake: Andrew Rose recently published a provoking paper, which shows that the choice of the exchange rate regime has had little influence on

What’s at stake: Andrew Rose recently published a provoking paper, which shows that the choice of the exchange rate regime has had little influence on economic outcomes in the Great Recession. While the empirical analysis of the paper excludes EMU countries, this result has challenged the consensus that life outside the euro would have been easier for periphery countries. Paul Krugman even wrote a new paper with a full-fledged New Keynesian model to counter the argument and to show that the effect of a sudden-stop under a floating exchange rate ought to be expansionary.

The new Andrew Rose paper on currency regimes

Antonio Fatas writes that the benefits and costs of different exchange rate regimes is one of the most debated topics in international macroeconomics and it is crucial for a very important decisions that policy makers regularly face on how to manage exchange rates. The 2008-09 crisis and the dismal performance of some Euro countries have reopened the debate about what life would have looked like for some of these countries if they had stayed out of the Euro.

Andrew Rose writes one might reasonably expect floating with an inflation target to be a diametrically opposed monetary regime compared with a durable hard fix, especially for handling the shockwaves that spilled out from the large economies as a consequence of the global financial crisis. The magnitude of the business cycle does not seem to have varied significantly between inflation targeters and hard fixers over the period since 2007. But in a much discussed new paper, Rose finds that this decision has been of little consequence for a variety of economic phenomena, at least lately. Growth, the output gap, inflation, and a host of other phenomena have been similar for hard fixers and inflation targeters in the period of and since the global financial crisis. That is, the "insulation value” of apparently different monetary regimes is similar in practice.

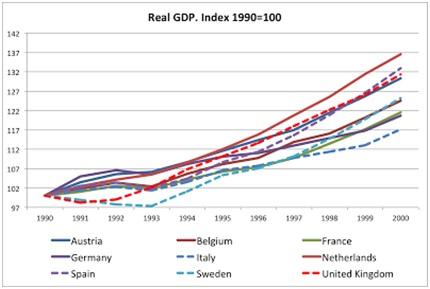

Antonio Fatas notes that the European countries were in a crisis also during the years 1991-1993. A crisis that brought their system of fixed exchange rates down. Some countries abandoned the fixed exchange rate and devalued while others stayed. This is the closest we have to an experiment of countries leaving the Euro area (yes, the experiment is not perfect, the crisis was much smaller, but it can help us understand the role of exchange rates). But the chart below reveals that there is no clear pattern between those who let their currencies devaluate (dotted lines) and those who did not. Growth differences do not seem to correlate well with the behavior of exchange rates. Euro countries have certainly suffered from being part of the Euro area not so much because they lost their ability to control their exchange rates, but because they ended up adopting the wrong policy mix.

Source: Antonio Fatas

Discussing the Rose results

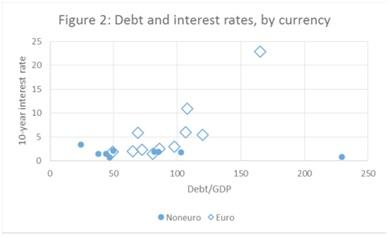

Paul Krugman writes that Andrew Rose doesn’t offer reasons why this doesn’t matter; he just offers a reduced-form relationship between currency regimes and economic performance, and fails to find a significant effect. Is this because there really is no effect, or because his tests lack power? The very striking empirical observation that debt levels matter much less for countries with their own currency than for those without should make us pause before we buy the Rose results.

Source: Paul Krugman

Scott Sumner writes that the fundamental criticism of fixed rates regimes is not that they produce slower growth on average, but rather that they lead to greater variability. Instead, what you would expect is that the economic performance of floating rate regimes as a group would show less variability than the economic performance of individual countries within a fixed rate regime. Actually even that is perhaps an excessively rigorous test, because single currency zones tend to be composed of countries with similar structural characteristics.

Tyler Cowen writes that Andrew Rose’s finding should not come as a surprise, for a few reasons:

- Floating rates can be tough on countries which import a lot of oil, or which import critical inputs for their production or exports.

- A lot of countries in 2008-2009 did not experience a traditional AD-only shock, rather they experienced trade shocks, which for the purposes of macro are like real shocks. Floating rates offer less protection against real shocks than against nominal shocks.

- One of the benefits of floating rates is that a country can crank up the rate of price inflation when it needs to, to offset negative demand shocks. If you are targeting an inflation rate, you are not doing this and that means you lose out on a potential benefit of floating rates.

The effect of a sudden-stop under floating exchange rates

I reviewed some of these arguments a couple of weeks ago in the blogs review on the expansionary effect of bond vigilantes. Early this week, Paul Krugman aired a new paper detailing his view on the subject.

Paul Krugman writes that a loss of foreign confidence produces a sudden stop – a sharp decline in the capital account. This must necessarily be matched by an equally sharp rise in the current account. But the mechanism of the required rise in the current account is crucially dependent on the currency regime. Under fixed rates, interest rates must rise enough to achieve the current account change through import compression. Under floating rates, the adjustment takes place through depreciation and export growth. As a result, a shock that is contractionary under fixed rates or a common currency is actually expansionary under floating rates.

Antonio Fatas writes that his argument is that in cases where countries have been running large current account deficit for years, a sudden stop of capital could be contractionary.

Brad DeLong writes the mechanism through which a sudden-stop can be contractionary does not apply to the industrialized economies of peripheral Europe in 2007. In a sudden stop, the central bank can make the economy awash in liquidity--it can credibly commit to keep the short-term safe nominal interest rate is at zero until the end of time--swap out cash and pull in bonds with abandon--and this will have no effect on the economy's real equilibrium. Why not? Because in a sudden stop, on the relevant margin government-printed cash is as unsatisfactory an asset as government bonds: it is not that people want to dump government bonds for cash or for foreign securities, it is that people want to dump both government bonds and cash for foreign securities, and also that economic chaos is so great that foreigners are unwilling to increase the amount of their own currencies they trade for either currently-produced domestic goods and services or domestically-located property. But that requires an extraordinary degree of dysfunction: not just a reduction in foreign exchange speculators' views of the long-term fundamental value of the currency, but a shutting-down of all margins on which changes in present and expected future monetary policy have any effect on the long-term real interest rate, and on which changes in the exchange rate drive changes in foreign purchases of anything domestic. There are countries and eras in which this sudden-stop mechanism is at work--where monetary policy loses its ability to affect domestic real interest rates and where economic chaos means that exchange-rate depreciation no longer leads to greater foreign purchases of either currently-produced goods or domestically-located assets--but those are countries with very large foreign currency-denominated debts and countries already near the edge of hyperinflation.