What does the Big Mac say about Euro Area adjustment?

The Big Mac Index offers some quick insights into the state of currencies around the globe by comparing the price of Big Macs across countries. Of cou

Update July 2013: 'What does euro area adjustment mean for your Big Mac (index)?'

The Big Mac Index offers some quick insights into the state of currencies around the globe by comparing the price of Big Macs across countries. Of course, the Big Mac index was never intended as a precise gauge of currency misalignment, as the Economist has just reminded us in its latest update. According to them, it is just about making PPP and other difficult exchange rate concepts more digestible.

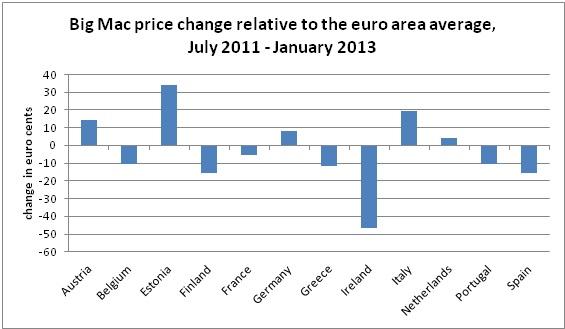

Well, in the euro area, we have the euro to be able to simply compare prices across the euro area. So how have Burger prices moved recently? Are prices in the euro area adjusting? Should we be pessimists or optimists on the adjustment challenge in the euro area? Since July 2011, the Economist has also been collecting the individual prices of Big Macs in major euro area countries. Let’s first look how they have developed in the different countries relative to the euro area average:

Source: Bruegel computation based on data compiled by the Economist.

I’d say, there are some good news here. Austria and Germany grow above average, while Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain are below average. Even France is below average. So adjustment seems to be working not just for unit labour costs but even real prices adjust[1].

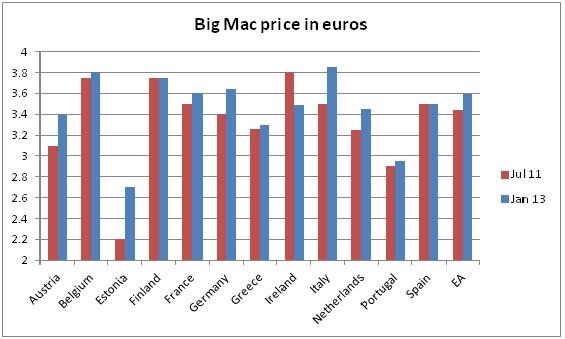

However, not all appears to be rosy. Burger prices in Italy have increased much more than anywhere else except for Estonia. But perhaps Italy is just catching up? Let’s look at the levels:

In fact, the Big Mac tells us that Italy is the most expensive place in the euro area. A Big Mac costs €3.85, while it costs only €3.6 in France and 3.64 in Germany. Or to put it in percentages, in July 2011, Italy was overvalued by 2.9% while in January 2013, it was overvalued by 5.7% relative to Germany. Of course, you may just as well say that Germany was undervalued… but then, the adjustment in Germany seems to go in the right direction but not in Italy in these last one and a half years.

Of course, one may argue that the Big Mac is a very special kind of food in the land of Pasta & Chianti. And of course, there has been quite some reporting last year that Italians are reducing their spending on food. So are Big Mac prices special because Italians substitute high end food with BigMacs? A quick look at a broader set of prices, namely the harmonized consumer price index, show that this is not a special Big Mac story. Italy had the highest inflation in the euro area from July 2011 to end of December 2012: prices were rising by more than 6%, while in the euro area they were increasing by only 3.9%. Well, perhaps all we capture are the tax increases that Italy put in place to adjust its public finance trajectory? A quick look at the HICP at constant taxes published by Eurostat again puts Italy at the top of the league with an increase of 4.8% during July 2011- November 2012 (the latest month with available data), while the euro area just increased by 2.9%. To be fair, HICP inflation in Germany undercuts the euro area rates – the Big Mac index doesn’t fully capture the missing price adjustment in Germany.

Overall, the Big Mac index shows some adjustment in the euro area in the last 18 months but Italian inflation rates are worrying. Labour market reforms that do not translate into lower product market prices are detrimental to consumers and prevent the economy from gaining export strength. Italy needs to apply the right policies to address high inflation.

[1] On the link between ULC and CPI, see Guntram Wolff, Arithmetics is absolute, Bruegel Policy Contribution.