Blogs review: India in trouble?

What's at stake: The emerging economies are currently being watched with increased anxiety in the context of the possible harmful effects of mone

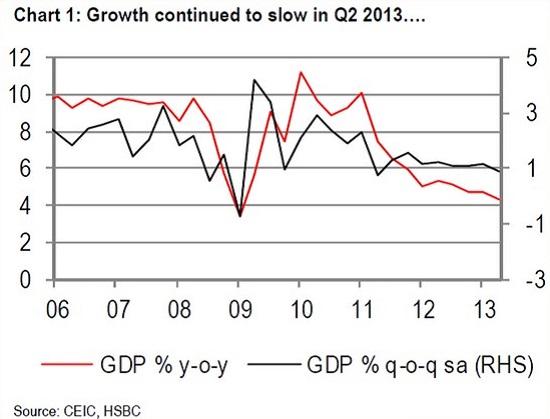

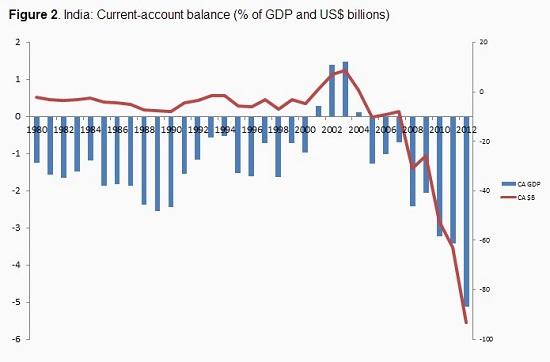

What's at stake: The emerging economies are currently being watched with increased anxiety in the context of the possible harmful effects of monetary policy tightening in the US on their ability to serve as the world’s growth engine (see last week’s blog review). India is under particular scrutiny at present. With a reduced reform momentum ahead of the 2014 general elections, expected GDP growth slowed to around 4% for 2013 – down from an average of around 9-10% in previous years – a widening current account deficit of now 5% of GDP and increased controls for capital outflows by Indian individuals and firms, some commentators are afraid the “Hindu growth rate” of 3-4% during the 90’s may be about to return.

The growth slowdown

Avantika Chilkoti at the FT’s Beyond BRICS comments that the downward revisions of growth forecasts – HSBC revised its 2013 forecast down to 4% from 5.5% and several leading indicators including business sentiment indices have also fallen – reflect that policy currently does not support growth. The Reserve Bank of India is more preoccupied with stabilizing the currency than supporting growth through lower rates. Structural reforms have been announced not been implemented. And government spending is unlikely to prop up demand as the focus is now on meeting the fiscal deficit target of 4.8 per cent of GDP. The only glimmer of hope for the short run is that the depreciating currency will further support exports – which were up by 12% in July compared to last year.

Source: FT, Beyond BRICS

Marco Annunziata writes that with the recent depreciation of the rupee versus the Dollar, India is a victim of deteriorating external circumstances – but not an innocent one. Its economic growth shrunk when economic reforms lost momentum. At the same time, its current account deficit widened rapidly to about 5%. A continuation of liberalisation policies in key sectors of the economy as well as upgrading crucial infrastructure (particularly with regard to power generation and distribution) and improving the business environment are needed to prevent the growth rate falling back to the 3-4% Hindu rate of growth of earlier decades

Source: Marco Annunziata / VoxEU

Tyler Cowen muses that the halving of growth rates is a big shift. India may be an economy moving across multiple equilibria in which the passage of time shows that it “deserves” increasingly inferior expectations. The danger is that a weak response to the current crisis may lead to India sliding down to a yet inferior equilibrium in future.

Ricardo Hausman points out that for most emerging economies, much of the strong nominal GDP growth in the 2003-2011 period was not due to production increases, but due to terms-of-trade improvements, capital inflows and real exchange rate appreciation. It is reasonable to expect that terms-of-trade improvements - export prices growing stronger than import prices – are not an everlasting process and will not continue. And the Balassa-Samuelson effect of countries with stronger real growth also experiencing a real appreciation should also not be counted upon too strongly: The same dynamics that inflated the dollar value of GDP growth in the good years for these countries will now work in the opposite direction: stable or lower export prices will reduce real growth and cause their currencies to stop appreciating or even weaken in real terms. No wonder the party is over.

A Rupee Crisis?

Simon Johnson retells the generic story of emerging market vulnerability: capital inflows during a time of growth and easy access to international financial markets let the currency appreciate and lead to the development of a current account deficit. As shifts in financial market sentiment are bound to occur, the decisive question is, how strongly leveraged a country is when sentiments turn negative. India’s situation is made less severe by the rupee’s floating exchange rate and by the presence of ample foreign exchange reserves. But two dangers from the US are on the horizon: the Fed’s fiscal policy tightening will push up interest rates in the US and attract capital out of emerging countries and when the next political fight over the US budget ceiling looms, the resultant flight to safety will further lead to capital outflows from emerging economies.

Paul Krugman is not very alarmed by the depreciation of the rupee: Yes, the rupee and other emerging market currencies depreciated a lot in a short time in mid-2013. But this may just be a correction of a previous overshoot due to capital inflows during a time of market euphoria. More importantly, India is not in the situation of the South-East Asian countries in the 1997-1998 or Argentina in 2001 with huge external debt overhangs – in fact, India’s external debt is rather small, less than 20% of GDP. Unless he’s missing something, the depreciation will lead to a temporary spike in inflation but not much more. Ashok Rao replies to this that India’s heavy dependency on 90% imported oil may be what Krugman misses. A strong, inelastic import demand for oil reduces the attractiveness of rupee depreciation as increases in the price of imported oil need to be weighed against export growth.

Devesh Kapur and Arvind Subramanian dispel some misdiagnoses of India’s current predicament. It is not a case of unsustainable public debt, a pure cyclical slowdown or a dangerous external debt level. Particularly the latter is important: That India’s external debt is actually relatively small means that allowing the currency to depreciate would improve the current account balance without creating debt service problems. In the short run, policy must have three goals: Increase growth, rebalance the current account and fight rising inflation. A loose monetary policy should achieve the first two aims, whilst a tightening of fiscal policy is required to keep inflation in check. As a reduction in government consumption is quite unlikely, a temporary import surcharge with a definite timetable for its phasing-out may be a more realistic third-best way of achieving this.

Capital controls

On 14th August, the Reserve Bank of India introduced two measures to reduce the ability of Indians to take capital out of the country: The limit on personal remittances was cut from $200,000 to $75,000 per year. And companies may now not spend more than their own book value on direct investments abroad, unless they have specific approval from the central bank. Previously they could spend up to four times their own net worth.

Anant Kala writes that these moves have raised concern among investors that India may implement broad capital controls to stem the plunge of its currency and of share prices. Although most see the RBI’s steps as measures to halt the rupee’s glide, it will be important to reassure investors that no broad capital controls will be implemented as particularly at this time, foreign investors, who would be deterred from investing in India by the expectation of having their capital locked up in India, are required to finance the rising current account deficit.

The Economist's Free Exchange blog writes that the aim of these measures was apparently to deal with incipient signs of capital flight by India’s rich. If India should be unsuccessful at convincing foreign investor that it has no intentions to implement capital controls that affect them, some real work has to be done to ensure India’s ability to finance its current account deficit. Measures such as an IMF loan or a dollar-denominated sovereign bond seem unlikely at present. Addressing the balance of payments by raising regulated prices on imported fuel and taxes on imported gold or eliminating a present ban on Indian iron ore exports would be sensible, but are controversial and take time. The current strategy of the government is to sit tight and hope for measures already taken to take effect. Keep your fingers crossed that they actually do.

Ryan Avent discusses Helene Rey’s Jackson Hole paper that argued for the presence of a “global financial cycle” in which the prices of risky assets, such as equities and corporate bonds, are correlated across the globe, regardless of exchange rate regimes. A monetary policy tightening in one country (i.e. the US) can translate into a capital flight from risky assets in India. Modest capital controls would only be the last resort, after linking the tightness of bank capital regulation to economic conditions, to help break this cycle. Capital controls can thus serve to maintain monetary policy independence – not unimportant at present, when a negative spillover from US monetary policy on Indian growth is to be expected and may indeed be one of the sources of India’s current problems.