Blogs review: The Bernanke doctrine and the separation between forward guidance and tapering

What’s at stake: In the US, a somewhat forgotten intellectual distinction between forward guidance and asset purchases has resurfaced following t

What’s at stake: In the US, a somewhat forgotten intellectual distinction between forward guidance and asset purchases has resurfaced following the June 19 FOMC talks of tapering. Until recently, the Fed had a precise state-dependent threshold for the future lift-off in short-term interest rates, but wasn’t specific about the timing for the tapering of its asset purchases. By providing specific forward guidance about asset purchases, the Fed has attempted to establish a distinction between these two tools. This has proven easier said than done.

A hard message to sell

Tim Duy writes that the Federal Reserve is having a difficult time convincing market participants that quantitative easing and interest rates represent two separate policy tools. They want to severe the perception that the two are connected - a reduction in the pace of asset purchases thus does not signal a change in the expected lift-off from the zero bound.

Ben Bernanke talked about the mix of instruments being used to provide the overall accommodation during the Q&A following his presentation at the NBER. The Fed has two instruments that we’ve been using in the context of interest rates close to the zero lower bound. The first, asset purchases, we have thought about, and I’ve frequently described as, providing some near-term momentum to the economy. In other words, we have said that we are trying to achieve a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market in the context of price stability. The second tool that we have is our rate policy, short-term interest rates, and associated with that is the forward guidance that we provided to the public about our expectations for when rates might change. There is some prospective gradual and possible change in the mix of instruments. But that shouldn’t be confused with the overall thrust of policy, which is highly accommodative.

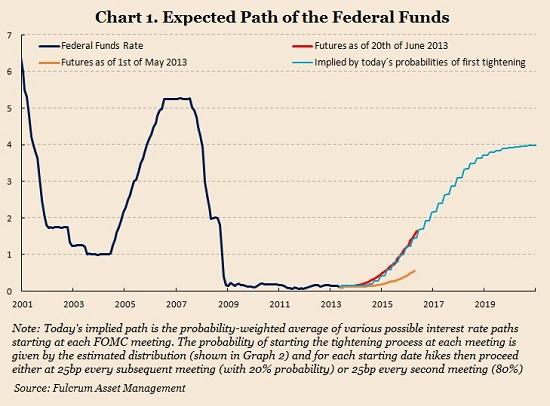

Paul Krugman writes that the Fed grossly misunderstood the nature of the relationship between its statements and market expectations. It believed that the market was listening closely to the details of what it said. In fact, the market doesn’t — and probably shouldn’t. Instead, it listens to the tone of Fed statements, and also Fed actions; it’s more a matter of character judgment than mathematics. And what the Fed conveyed with the tapering talk was a sense that its heart really isn’t in this stimulus thing. Gavyn Davies illustrates in the graph below that the markets have not yet indeed accepted this separation between the balance sheet and short rates.

Less QE, more guidance, and more disagreements

Jan Hatzius writes that Paul Krugman has the right explanation; merely repeating the current short-term interest rate guidance may not be sufficient to halt the selloff at the front end of the yield curve. And even postponing the taper by a couple of meetings might not be very powerful in reversing the damage to short-term rate expectations. A more promising avenue would be to strengthen the forward rate guidance—either an upfront reduction in the 6.5% unemployment threshold or a more explicit indication in the FOMC statement that unexpected weakness in inflation and/or labor force participation will result in a lower threshold.

Joe Weisenthal writes that Bernanke didn't quite change the threshold for where the first rate hike could be considered, but at a Q&A following his NBER presentation he all-but moved to a more dovish stance on keeping interest rates low for a long time. He said, for example, that the current rate of unemployment was probably understanding the labor market weakness, due to the low participation rate. And he promised that after unemployment fell to 6.5%, rates would still stay low for quite some time. It seems very likely that the Fed will basically do what Hatzius suggests, move down the Evan's Rule threshold.

Tim Duy picked up an interesting point from the Fed minutes: there was no discussion inside the FOMC for a 7% unemployment trigger for tapering asset purchases, unlike what Bernanke said. So where did that number come from? Must have been Bernanke revealing his own preference. This was confirmed by Bullard who said that when Mr. Bernanke said the bond buying program will likely end when a 7% jobless rate is achieved, he was not stating official FOMC policy. The committee itself has not voted on or approved any threshold for the [bond buying] program. It’s not clear we would.

Wallace Neutrality redux

Stephen Williamson notes that this distinction isn’t new and that the Fed has consistently segmented QE from forward guidance, particularly in the FOMC statement. It even has segmented different kinds of QE (reserves for long Treasuries, short Treasuries for long Treasuries, reserves for MBSs) arguing that these are different tools. Does it now think that one type of intervention is preferable to another, or that there were different circumstances along the path we have followed since the financial crisis that warrant different approaches? None of that is clear from Fed communications. The only explanation we have is that these are different tools, and that when you have a lot of tools and you're in a predicament, you should use them all. Maybe there's little difference among the effects (if any) of these different tools. If so, the Fed is needlessly confusing us. Williamson also notes that there is no explanation whatsoever about where the $85 billion per month number comes from, which makes him suspicious that they simply don’t know.

Mike Konczal notes that it is useful to revisit the debate about the impact of the steps the Fed took in 2012 to understand how changing the mix of instruments will work. To recap, the Fed took two major steps in 2012. First, it used a communication strategy to say that it would keep interest rates low until certain economic states were hit. Second, the Fed started purchasing $85 billion a month in assets until this goal was hit. In his major September 2012 paper, Woodford (see also our previous review on Wallace Neutrality) argued that the latter step, the $85 billion in purchases every month, doesn't even matter, because "'portfolio-balance effects' do not exist in a modern, general-equilibrium theory of asset prices." So moving future purchases up or down at the margins, keeping the expected future path of short-term interest rates constant, shouldn't matter either.