Abenomics: the implications for Europe

For two decades the Japanese economy has been mired in deflation and stagnant nominal GDP. Real GDP and per capita GDP have grown a bit but only thank

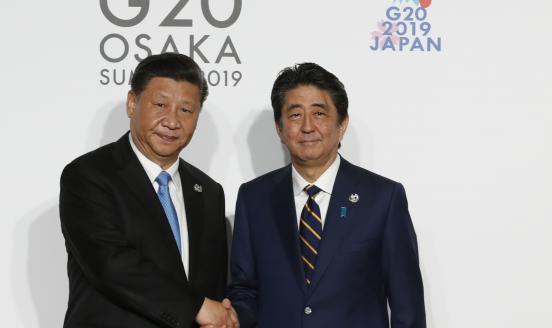

For two decades the Japanese economy has been mired in deflation and stagnant nominal GDP. Real GDP and per capita GDP have grown a bit but only thanks to chronic fiscal deficits that have brought gross public debt to well over 200% of GDP. The new government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has decided to end this situation by adopting an economic strategy (“Abenomics”) involving three measures: fiscal expansion, monetary easing and growth-enhancing structural reforms.

The three legs of the strategy have now been adopted or announced. In January 2013, barely a month after its election, the new government adopted a fiscal stimulus of Y10.3 trillion (€85 billion) equivalent to about 2% of GDP. In April the Bank of Japan under the leadership of its new governor Haruhiko Kuroda launched quantitative and qualitative monetary easing aimed at fulfilling the PM’s goal of 2% inflation within two years. And finally in early June PM Abe announced a series of measures to boost Japan’s long-term economic performance.

Until late May, the plan seemed to be working well. The Nikkei 225 stock market index had risen by more than 40% since Shinzo Abe was elected prime minister in December 2012 and by more than 60% since he was elected opposition leader on his Abenomics platform three months earlier. Also GDP growth forecasts for 2013 and 2014 for Japan were revised upwards by the IMF in April. As a result, the PM was enjoying a high approval rating that should have enabled him to announce bold structural reforms to boost growth. Unfortunately, the measures revealed so far have been disappointing. Coming after a series of stock market falls which may have been purely technical, the measures led The Economist (June 15th-21st 2013) to declare that perhaps “Abenomics was already fizzling out”, though it also stated that “it is still too early to write off Abenomics”.

The international community has been watching Abenomics with great interest. Although somewhat worried that the yen has depreciated against other currencies by nearly 20% since Mr. Abe came to power (and by about 30% since he was elected opposition leader), it obviously views positively the potential revival of the world’s third largest economy. In Europe the reaction to Abenomics has generally been positive as well. But concerns about the external value of the yen are also present because the economic situation here remains worrisome, with annual GDP growth in 2013 expected at -0.1% in the European Union and at -0.4% in the euro area. Both the hope of future Japanese accelerated growth and the apprehension about further yen depreciation are magnified by the prospect of more intense EU-Japan trade relations if the negotiations on a bilateral free trade agreement launched in March are successful.

Stronger demand growth in Japan should translate into higher exports for EU suppliers who would further benefit from the EU-Japan FTA when it is implemented. This might reverse the recent downward trend in the share of Japan as a destination of EU goods exports, which has fallen from 5.4% in 2000 to 3.3% in 2012. How much of this potential will be undermined by a weaker yen obviously depends partly on how much the yen depreciates against European currencies. The more it depreciates the more also it would boost Japan’s exports potentially to the detriment of EU production.

On June 21, the yen was at 98 against the dollar and 128 against the euro, compared to, respectively, 78 and 100 on September 26, 2012, when Mr. Abe became leader of the opposition and contender for the post of prime minister under the banner of Abenomics.

Will the fall of the yen continue?

Japanese analysts generally regard the yen’s recent depreciation an adjustment of the overvaluation which emerged under the extreme strain of the global financial market after the Lehman shock, and view its current level “fair”. At the same time, they consider further depreciation problematic, because it might annoy other nations and because it would be harmful to the Japanese economy which is heavily reliant on dollar-invoiced energy imports.

The IMF apparently shares the view that the current yen level is “appropriate”. Yet with currency strategists (such as Alan Ruskin at Deutsche Bank and Beat Siegenthaler at UBS) predicting a yen at 110 against the dollar by year-end international dissatisfaction may be brewing. Two recent developments point in this direction.

First, the US Treasury has on several occasions warned that it is “closely monitoring” Japan’s economic policies to ensure that it refrains from competitive devaluation and targeting its exchange rate for competitive purposes. Second, on May 9 the Bank of Korea unexpectedly cut interest rates, citing the damaging effect the weaker yen is having on its exports. The same week, New Zealand’s central bank admitted intervening in the currency market to try to weaken its dollar, which has come under pressure in part because of the weaker yen. Moreover, Australia cut interest rates, having previously warned that its exchange rate was too strong. If this move were followed by a significant depreciation of the Korean won, and perhaps of other Asian currencies, like the Taiwanese dollar, it would likely raise concerns not only in the United States but also in Europe. Depreciation of the Chinese yuan is, however, generally regarded as less likely, both because it could fuel financial instability in China and because of the fear of trade retaliation.

So far, there has been little official (or otherwise) reaction in Europe about Abenomics and its consequences, except to say, as European Central Bank President Mario Draghi did in April, that Japan’s policy of monetary easing is “determined by domestic policy considerations” and that “there is no currency war.” In part this is due to the fact that last year Japan only accounted for only 3.6% of EU merchandise imports and 3.3% of EU exports (compared to, respectively, 9.3% and 5.4% in 2000). As a result, despite an appreciation of nearly 30% of the euro against the yen since September 2012, the Bank for International Settlement estimates that the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro has appreciated by only about 5% thanks to the euro’s depreciation against a number of other currencies, including the US dollar, the Chinese yuan and the Korean won. This is not very much but it certainly adds to the burden of those eurozone countries that are already struggling with high debt and low competitiveness levels.

But the main potential effect of Abenomics on Europe lies elsewhere. If PM Abe decides after all to adopt ambitious growth-enhancing measures and Abenomics proves successful, the most important implication for Europe will be that reviving the economy requires a combination of bold macroeconomic and structural policies, with the right sequencing between the two.

This comment is based on a paper presented at the Economic and Social Research Institute of Japan.