A black market in Cyprus? Lessons from Venezuela

Wherever the government builds fences the market will place stairs to climb them. On March 28th, the Cypriot government imposed capital controls as a

Wherever the government builds fences the market will place stairs to climb them. On March 28th, the Cypriot government imposed capital controls as a measure to avoid bank runs and financial instability in the small euro zone country, but so far there is very little evidence on the existence of a well-functioning black market in Cyprus.

In almost every case where capital account restrictions were imposed, a parallel or black exchange rate market arose[1]. Current cases of black exchange markets include Argentina where exchange controls were put in place in 2011 in the same fashion than the Venezuelan exchange rate controls which are in place since 2003. Both governments defend overvalued[2] exchange rates by restricting the amounts and conditions in which their residents can purchase foreign currency. But these are not isolated cases, especially in the developing world, other recent and current cases of parallel and multiple exchange rates according to Ilzetzki, Reinhart and Rogoff (2011) include Egypt, Gambia, Guyana, Haiti, Libya, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Peru, Russian Federation, Suriname, Swaziland, Syria, Turkmenistan, Vietnam and Zambia.

Advanced economies are not immune to the surge of black markets either: Iceland has controls over capital outflows since 2008 and despite the lack of data, there is some evidence of the existence of a black market.[3]

As an illustrative example: how does the black market work in Venezuela?

The Venezuelan financial system is completely isolated from the rest of the world by an exchange control system that renders it technically impossible to make any kind of payment between a bank account abroad and one inside the country, or to use local credit cards abroad or online without requesting permission to the commission of administration of foreign currency (CADIVI). Until May 2010 Venezuelan bolivars could be freely and legally exchanged with foreign currency in brokerage houses through the use of a few financial instruments that could be traded in the local market in local currency and on foreign market in foreign currency. But thereafter this parallel market also known as swap dollar (dólar permuta) was declared illegal and it was immediately replaced by an illegal black market.

In the current black market, two parties agree on an exchange rate (there is no trustable reference of the price anymore since it also became illegal to be disclosed in any media) and based on trust that one of them will transfer funds in local currency from her Venezuelan account to the other party’s Venezuelan account while the other would do the same from her foreign account to the other person’s foreign account in foreign currency at the agreed exchange rate; in this sense the transaction does not go through the balance of payments, is just a local transfer of funds with a counterpart in some external market. Of course as the system is based on trust and there is no legal basis on these verbal contracts scams are at the order of the day.

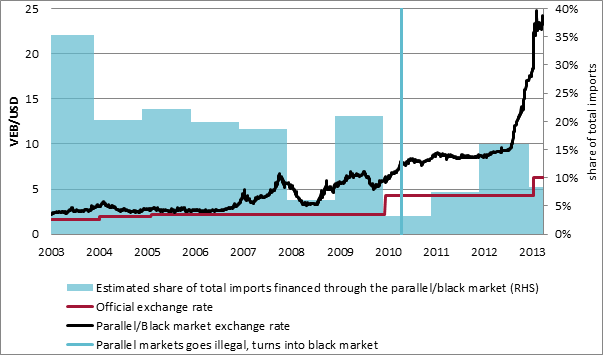

In the following graph the blue shaded bars show the estimated share of total Venezuelan imports that were paid through the parallel market; despite its illegal character (since May 2010: vertical line) the black market keeps financing a non-marginal share of total imports. The spread between the official and parallel exchange rates gives an idea of the potential profits that can be obtained by illegally diverting funds from one market to the other.

Venezuelan bolivar exchange rates

Sources: Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV) and Ecoanalítica

How would a black market work in Cyprus and why don’t we see it operational so far?

Usually, exchange controls imply restrictions on the purchase/sale of foreign currencies by residents and/or on the purchase/sale of local currency by nonresidents. In the case of Cyprus the local and the foreign currency could be the same one: “euro”, but because funds held in Cyprus cannot be freely transferred abroad, Cypriot euros can be considered a different and less valued currency than the rest of the euros.

One big difference between the Cypriot and other exchange and capital controls is that the Cypriot government also imposed restrictions on transactions within the Republic of Cyprus unless they are made within the same credit institution.

These additional restrictions are currently set at €10,000/€50,000 per natural/legal person per month per credit institution, plus the prohibition of opening new accounts to customers unless they are already customers of that particular credit institution[4] make the development of a black market much more difficult, though not impossible. Only two parties with bank accounts in the same institution inside Cyprus and bank accounts abroad could perform a swap of local and foreign funds for an amount superior to the before mentioned monthly limit.

Another black market that could be developed is the swap of frozen Cypriot deposits by liquid funds abroad; there is some evidence of something like this going on already but there are legal limitations to be solved in order to enforce the contracts of this kind of swaps once the Cypriot deposits are unfrozen.

Since the 25th of April, when the tenth decree for temporary restrictive measures on transactions was published, cashless payments or transfers within Cyprus for the purchase of goods and services are allowed without the approval of the Committee, by presenting the relevant supporting documents, before this was only possible for an amount smaller than €300,000. Relaxing the restrictions on transactions is a positive sign, also with a view to prevent potentially emerging corruption.[5]

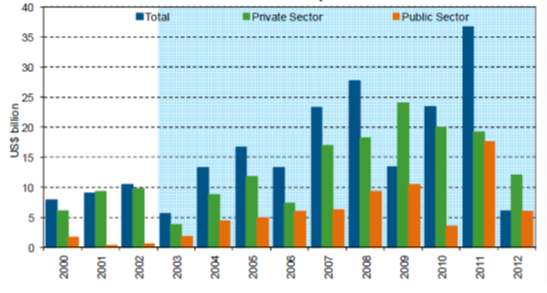

In more than 10 years of exchange controls in Venezuela finaglers have found every flaw in a system that is continuously amended as the government notices the weak points only to become aware that capital outflows keep increasing year by year.

Capital outflows from Venezuela

Note: the blue shadow indicates the start of the exchange control

Sources: BCV and Ecoanalítica’s calculations

Conclusion

Wherever the government builds fences the market will try to create stairs to climb them. Several studies (Rogoff 2002, Forbes 2007, Ewards 1999, Danielson 2013) have shown that controls on capital outflows are not only ineffective but they also generate incentives to corruption as they create arbitrage opportunities that some economic agents are willing to take as long as the profitability justifies the risks taken. The Cypriot government should continue to ease the restrictions on transactions as it has been doing so far and end with the capital controls sooner than later, before it creates further distortions and perverse incentives.

References

Chinn, M. and Ito, H., (2007), “A new measure of financial openness”. Journal of Development Economics, 2006.

Danielsson, J. (2013) “The capital controls in Cyprus and the Icelandic experience”. VoxEU.org, 28, March, 2013.

Edwards, S., (1999), “How effective are capital controls”. National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper 7413, November, 1999.

Forbes, K. (2007), “The microeconomic evidence on capital controls: no free lunch”, in Edwards, S., (2007), Capital controls and capital flows in emerging economies: policies, practices and consequences, (p. 171 – 202). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ilzetzki, E., Reinhart, C. and Rogoff, K., (2011), “The country chronologies and background material to exchange rate arrangements in the 21st century: will the anchor currency hold?”. Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(1):1-48, February 2004.

Rogoff (2002), K., “Straight Talk -- Rethinking capital controls: When should we keep an open mind?” Finance Development: a quarterly magazine of the IMF. December 2002, Volume 39, Number 4.

[1] We look at the exchange rate arrangements database built by Ilzetzki, Reinhart and Rogoff (2011) and matched it with the capital account openness index created by Chinn and Ito (2007)

[2] According to the last update of the economist big mac index, the Venezuelan currency was the most overvalued in the world as of January 2013, and even though it was devaluated by 46% in February it is still highly overvalued

[3] Jon Danielsson and Ragnar Arnason published interesting articles at VOX criticizing capital controls in Iceland: Capital controls are exactly wrong for Iceland and The capital controls in Cyprus and the Icelandic experience

[4] http://www.centralbank.gov.cy/media//pdf/TenthDecree_EN_25042013.pdf

[5] In particular, the CBC is aware that this kind of transactions is prone to be used to circumvent the restrictive measures and in their sixth decree states: “It should also be clarified that the relaxation of restrictions on cashless payments and money transfers for amounts up to €300.000 was made in order to facilitate transactions within the Republic of Cyprus and not to transfer funds from one institution to another. Hence, the provision of paragraph 3 (i) of the Decree is pertinent here, which states that it is prohibited for any credit institution to make payments or transfers which aim to circumvent the restrictive measures.” But the penalty for evading the restrictions is not clear.