The Euro Crisis: Mission Accomplished?*

High unemployment, bleak economic outlook, high public and private debts, dysfunctional banks, weak competitiveness, and an unfavorable external envir

High unemployment, bleak economic outlook, high public and private debts, dysfunctional banks, weak competitiveness, and an unfavorable external environment are just a few of the challenges facing southern members of the euro zone. Despite these hurdles, the ever-optimistic European Council and other leaders said in January that the euro crisis had bottomed out. Herman Van Rompuy, the president of the European Council, proclaimed, “The worst is behind us, in particular the existential threat to the euro.” Then there was Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank (ECB), who declared that “the darkest clouds over the euro area [have] subsided.”

Certainly, market pressures have eased significantly since late July 2012, when Draghi delivered his remarkable “whatever it takes” speech, pledging to use every means available to a central banker to stabilize the euro, at least within the mandate of the ECB. And he said that to the extent that government bond yields are too high—not because of the risk of default or low market liquidity, but due to speculation over a possible exit of some country from the euro zone or an end to the euro entirely—they fall within the mandate of the ECB. Since then, Italian and Spanish bond yields have fallen, and the credit default swap spreads of their non-financial corporations have narrowed—a prime measure of confidence in a nation’s corporate system. At the same time, stock prices have risen throughout Europe; deposits have started to return to Greek and Spanish banks; reliance on ECB funding of European banks has been reduced, which likely signals some normalization of the euro area financial markets.

The improvement in financial stability is real, but the clear analogy, unfortunately, is to President George W. Bush, who in 2003, stood on an aircraft carrier beneath a banner that read, “Mission Accomplished,” only two months into an Iraq war that would last another decade. The dark clouds of euro crisis are hardly behind us.

Betting the euro

The improvement in market sentiment is likely supported by a number of factors. Most importantly, market participants, losing money betting against the euro may have learned that facing an abyss, European policymakers always come up with something to save the euro, even if only for a few months. Indeed, European leaders may continue to behave this way, should the euro face a renewed threat.

There was also significant progress in building new initiatives in the euro area in 2012. Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech was followed by the launch of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs)—the unlimited purchases of government bonds of all euro member states that meet the conditions of a financial assistance program. Integration of banking oversight started with a decision to centralize supervision of major banks. The treaty on the euro area’s permanent rescue fund, the European Stability Mechanism, was ratified. And a large number of reforms aiming to more strictly control fiscal accounts of euro area member states and their economic policies came into force. While it may be appropriate to question whether these are the proper responses to the euro crisis, the progress is undeniable.

Finally, we saw the beginnings of the adjustment of trade imbalances—the deficits of southern euro members declining in tandem with German surpluses vis-a-vis euro area partners. The export performance is now strong in Ireland, Spain, and Portugal, while labor costs have fallen.

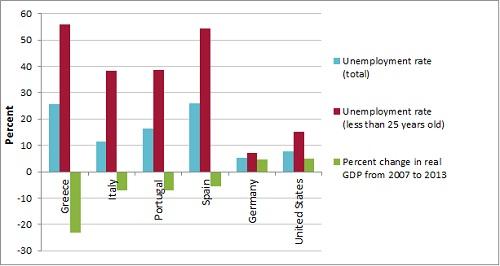

Less clearly visible, however, is that the fundamental problems of the southern member states remain. While growth is weak everywhere in the euro area, the outlook is particularly gloomy in southern Europe. Unemployment rates continue to skyrocket, reaching 25 percent in Greece and Spain, while the jobless rate of youths exceeds 50 percent. About every second young person who wishes to work cannot find a job. Social unrest, already high in Greece, is on the rise in other southern euro members.

Figure 1: Unemployment rate in December 2012 and the change in GDP from 2007 to 2013

Source: Eurostat. Note: the 2013 GDP forecasts are based on the European Commission’s autumn 2012 forecast. For Greece, the unemployment rate data are for October 2012.

At the same time, public debts are high and calls for further significant fiscal adjustments (in the form of expenditure cuts and tax increases) are likely to depress demand, even if the pace of such adjustment is allowed to slow. Private debts are also high. Moreover, the collapse in output as a result of reduced consumer demand and available credit, accompanied by rising unemployment has led to widespread bankruptcies, causing further losses to the banking sector, which financed many of these companies in rosier times. It is getting to the point where banks cannot serve their main role of providing credit even to viable companies. In Spain, loans to non-financial corporations declined 18 percent from late 2008 to late 2012, but factor in inflation and the real decline in credit is 25 percent. The European financial landscape is bank-dominated with only a minor role for the securities market. In Spain, some 99 percent of credit to non-financial corporations comes from banks, barely 1 percent from securities markets. Issuing corporate debt cannot come close to compensating for the drop in bank lending. All of these factors are set to depress domestic demand in the foreseeable future.

As for external demand, the sectors producing goods and services for export are struggling in southern Europe. Their share of the total economy is low—about 10 to 14 percent of GDP in contrast to more than 20 percent in Germany and Ireland—and their competitiveness is weak. Wages simply grew too much, too fast for years before the crisis. This feeble southern export sector faces modest demand inside the euro area and an appreciating euro exchange rate, which makes exports outside the euro area less profitable. The appreciated euro is due partly to the improvement in euro area financial stability, and partly to the ECB’s rather conservative policies at a time when other major central banks, like the U.S. Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and more recently the Bank of Japan (giving way to pressure from the recently elected Prime Minister Shinzo Abe) engage in massive quantitative easing.

The EU's reponse

Europe’s answers to these problems include structural reforms; greater coordination of economic, fiscal, and financial policies; a “compact for growth and jobs”; and provisions for widespread ECB liquidity measures.

No doubt, structural reforms are indispensable to revitalizing the public sector and fostering a positive business environment. Some argue that the public sector in Greece is even less efficient than the public sectors of former communist countries before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Before the crisis, the Greek railway had more employees than passengers, and its annual income from ticket sales was less than one-sixth of the wage bill of the company, making for a billion euro loss each year. A former minister, Stefanos Manos, has pointed out that it would’ve been cheaper to put all the commuters into private taxis. Similar inefficiencies characterize other state institutions as well. Tax evasion is rampant. Antiquated regulations constrain competition and enterprise growth, while preventing an effective adjustment of employment in individual companies faced with shocks.

So there is no question that widespread structural reforms must be implemented in Greece, as well as other southern euro members. But it will take a long time before structural reforms can take effect, and in the short term, they may even intensify problems. If regulations on worker firings are relaxed—streamlining businesses and government offices—unemployment is likely to increase in the short term.

More coordination of economic, fiscal, and financial policies may make some sense in the European environment. In other monetary unions, such as the United States, individual states do not coordinate these policies, since policy mismanagement in an American state has a smaller impact on other states than the impact of policy mismanagement in a euro area country on the rest of the euro area. Also, in the United States there is a strong federal government with ample financial resources and a broad latitude to intervene across the country, thereby helping smooth the impact of economic shocks. But Europe lacks this politically and financially powerful center. Plus, the latest crisis demonstrated that national policymakers in the euro area are not always able to follow sensible strategies. Little was done in Spain and Ireland to curb skyrocketing housing prices that preceded an unusually large expansion of the construction sector before the crisis. More coordination can help member states design their own structural policies, but again, this is not likely to change the bleak economic outlook of southern Europe in the near future.

At last June’s summit, European leaders agreed to a “Compact for Growth and Jobs” that targets structural reforms, completing the restructuring of the banking sector, growth-friendly fiscal consolidations, addressing the social consequences of the crisis, and deepening the single market. Unfortunately, a mere declaration of these goals does little more than raise awareness that these are important issues. Euro members have still not designed sufficient concrete measures to achieve these goals, but a few promising new tools have been mobilized. Most welcome is the provision of €10 billion in fresh capital to the European Investment Bank, increasing lending capacity by €60 billion, while launching a €4.5 billion pilot phase for project bonds. This will hopefully bring fresh private money to transport, energy, and information technology projects, supported by a guarantee of the European Union. These initiatives will likely have only a limited impact on growth in the European Union because of their small scale. The European Union’s multi-year budget also has various structural funds for development and social cohesion, as well as a significant portion of planned spending that has not yet been used. These idle funds will be reallocated to growth-enhancing measures. While important, this does not constitute new funding, and these measures—whatever they end up being—will progress slowly.

The ECB was the most efficient and successful European institution during the crisis. As early as 2007 it had already responded with various measures supporting bank liquidity when the economic crisis erupted in the United States, and the bank amended its arsenal later when it was needed more immediately. Also, by launching the OMT, it not only helped ease pressure on government bond markets but also contributed to the narrowing of the credit default swap spread of non-financial corporations, which had previously tracked their respective governments. The central bank also helped reverse the financial fragmentation of the euro area. Growth in Europe is not possible without a well-functioning banking system. So every measure that’s aimed at restoring the normal function of banks should help growth. The improvements of financial conditions should benefit southern euro members as well, but by itself, it’s unlikely to transform the recession into recovery. Also, resisting more widespread use of non-conventional monetary policy tools, such as quantitative easing, at a time when most other major central banks deploy them, risks a strengthening of the euro, which would make it even more difficult for southern euro members to emerge from their current troubles.

The euro exit option

Given the major growth challenge of southern member states and the inadequate European response, one should wonder if these troubled countries, and the rest of the euro area as well, would be better off ejecting these weaker members. My answer is clearly “no”—though it would be better had these countries not joined the euro in the first place. This is now history, and everyone would be worse off by euro exits of any nation. There remains hope that, despite the mounting challenges, troubled members could adjust inside the euro area. In order for this to happen, Europe must implement a host of innovative policy measures.

It is impossible to provide an accurate estimate of the cost of an exit from the euro of even one member state, but it would most likely be huge. Analysts at the United Bank of Switzerland have concluded that an economically weak country leaving the euro area would lose about half its GDP in the first year. If they are correct, it is unclear how many years it would take to compensate for the lost output, even if growth were to increase from this halved level of output. The decline in output would necessitate even harsher fiscal austerity, as it is not very likely that, in the event of a messy exit from the euro, other euro area partners would be happy to lend to the departing country. Without such support, the government could spend only tax revenues, which would be dramatically reduced by the collapse in GDP.

There would also be longer-term consequences. The low credibility of the newly stand-alone central bank of the exiting country would likely lead to much higher real interest rates and a period of high inflation, which are bad for growth. Additionally, a euro exit may be accompanied by a departure from the European Union, depriving the country of EU financial transfers. Even more importantly, in the case of an exit, it would be difficult to safeguard other economically weak countries and a wave of exits could prove catastrophic, even for the economically stronger euro-area countries.

Since 2008, Spanish exporters have been the best performers among the 15 original European Union countries, who joined prior to 2004. Spain is followed by Germany, Ireland, and Portugal. (However, the export performance of Greece is very weak.) Spain and Portugal even outperform Britain and Sweden, two countries that benefited from significant currency depreciation during the crisis (since they retained their domestic currencies by remaining outside the euro currency zone). Presumably, the drastic reduction in domestic demand in hard-hit southern euro members raised pressure on companies to export. Some succeeded quite handsomely, partly by laying-off employees and thereby increasing labor productivity. While the Portuguese and Spanish export sectors remain small, their solid performance is an indication that their foreign trade sector has scope for expansion.

Research by the World Bank has found that large and internationalized firms in southern Europe are as productive as large firms in western and northern Europe. The main issue is that there are far fewer large firms in southern Europe, because of various regulatory barriers. This suggests that while business conditions are unfavorable and there are barriers to company growth, properly managed firms are able to achieve a high level of efficiency in southern Europe.

The to-do list

But much more needs to be done. Above all, southern European countries, suffering from vast structural weaknesses must engage in a number of efforts, including product and labor market regulations and shake-ups of public administrations. Moreover, while productivity has improved and unit labor costs have been falling in countries like Spain since 2008, this was mainly a consequence of reduced employment, which has adverse social consequences. Wages have proved to be downwardly rigid, meaning employers are reluctant to demand, and employees even more reluctant to accept, lower wages. Structural reforms to improve the functioning of labor markets are also inevitable, as are reforms to intensify competition in the domestic sector. Of course, it will take a long time for these reforms to take effect.

The southern euro countries must continue fiscal consolidation at an appropriate pace. When fiscal targets are not met due to weakened economic performance, responding with additional austerity measures just deepens the recession. Instead of setting nominal fiscal targets, such as the critical 3 percent of GDP deficit that’s been a target since the Maastricht Treaty created the Eurocurrency zone in 1992, the targets should refer only to the structural deficit, which is a measure of the deficit cleaned from the impact of the business cycle and one-time budgetary items.

There is also a strong case for wage increases in economically stronger euro area trading partners, like Germany, that would make southern European companies more competitive. Before the crisis, wages grew too fast in southern Europe and too slowly in Germany. As a result, a major competitiveness gap emerged between southern euro members and Germany. Since Germany is a major trading partner, restoration of the wage competitiveness of southern Europe is hardly possible without faster German wage growth. This has started to some extent, but much more is needed. In particular, a boost to German domestic demand by tax cuts or increased public expenditures would increase demand for labor, and thereby wages.

Fiscal expansion in economically stronger euro area members, or at least a significant slowdown in the pace of fiscal consolidation, would facilitate economic adjustment of the southern members. A more expansionary fiscal policy in Germany could also kick-start growth there, which would not only help southern members export more to Germany, but would also improve market sentiment toward the whole euro area, indirectly benefiting all members. Unfortunately, the relaxation of fiscal targets in northern Europe does not seem to be on the agenda due to their obsession with budget deficits.

A weaker euro would also greatly facilitate adjustment in southern euro area members, because the role of intra-euro trade has gradually declined, while the role of extra-euro trade has increased. In 2011, the initial 12 eurozone members represented 38 percent of German exports and 43 percent of German imports. The same figures for Spain are 53 percent and 47 percent, respectively, and for Greece considerably lower, 29 percent and 41 percent. The ever larger role of extra-euro trade suggests that a purely intra-euro adjustment strategy can only have a partial success. If extra-euro trade deficits of southern euro members do not improve sufficiently, then there should be a kind of overcompensation by massive improvement in their intra-euro trade balances. This in turn would require overly large wage increases in northern countries and wage declines in southern countries, which do not seem to be feasible. Too-fast wage (and consequent price) increases in Germany would be resisted, while wages remain downwardly rigid in southern Europe. A weaker euro would therefore help a lot.

Further interest rate cuts and quantitative easing by the ECB could foster a weaker Euro. But there is persistent talk about currency wars, harking back to what happened in the early 1930s when one country after another raced to weaken its currency. Some fear that any ECB action could risk renewing such a war today. Yet this argument stands on weak grounds, because the ECB has to do only what other major central banks have done, and not more. A weaker euro would help southern economies improve their trade balances with non-euro countries and would also boost German exports. This in turn would help address intra-euro imbalances, since increased exports would likely translate into greater wage increases in Germany because of its tight labor market. That would not happen in Spain, because of its already high unemployment. Therefore, a weaker euro exchange rate would not only help improve extra-euro trade balances but also help improve Spain’s competitiveness relative to Germany. Without a weaker euro, Spain would need to enter a deflationary period, which is difficult to achieve and would worsen both public and private debt sustainability even more.

As for the banking system, bad assets must be recognized and dealt with promptly, to support lowering burdensome debt in the non-financial private sector and restoring credit. Euro area partners should also recognize that public debt, at least in Greece, is still too high and the measures agreed to in December 2012, while pointing in the right direction, are insufficient. Since European partners have loaned money to Greece to repay private lenders, further easing the debt burden cannot be accomplished without European involvement. This should apply to all three official lenders—euro area partners, the ECB, and the IMF. This is the price official lenders must pay for their mistakes in managing the Greek crisis in 2010 and 2011. And, if the strategy is well-designed, Greece should be in a position to pay back the debt relief from future surpluses, realistically, beyond 2030.

Finally, to help break out of the downward economic spiral that southern euro area member states face, a very significant European investment program is needed for southern members. The European Investment Bank seems to be the best institution to carry out such an investment program, and therefore further capital should be provided to it beyond the €10 billion agreed at the June 29, 2012 European Council as part of its “Compact for Growth and Jobs.” Investments are different from aid and lending. The money should not be regarded as a transfer but as an investment into real assets that will generate an income and could be sold at a later date.

Is the worst over?

Market conditions have improved in the past six months, and there is much less talk about a euro breakup now. This is good news. But the hurdles faced by southern euro members remain, and there are still many risks along the long the path to full adjustment. For instance, if the recession continues to deepen in Greece, social tensions could escalate, which could lead to domestic political paralysis. Under such circumstances, cooperation between euro area partners and Greece, including the financial assistance that has already been granted, could come to an end, leading to an accelerated and uncontrolled exit from the euro area, causing devastating consequences across Europe.

Another key risk factor is Italy, which is the elephant in the room with its €2 trillion public debt. While Italy has been able to withstand the crisis reasonably well so far, if the policies of the new government to be formed after the February elections do not gain market approval, or if economic conditions deteriorate unexpectedly, a major crisis could break out. Italy would be “too big to save” by any standard financial assistance program, like the ones granted to Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. The only solution would be massive financing from the ECB, which would not be received well in Germany and other northern European countries and could provoke a European political crisis.

The single most pressing threat to the integrity of the euro area and the very existence of the euro is the depth of the recession in southern European member states. There are policy measures that would help stop the economic misery in these countries and offer the prospect for improved economic conditions, but most of them are not yet on the agenda. The existential risk to the euro is far from over. We are not yet at a “Mission Accomplished” position, which is realistic only when robust economic growth and job creation have resumed in all southern euro member nations.

* This article was written in January 2013 for the Spring issue of the World Policy Journal