Competition policy trends in South Korea

Economists often talk about a strong correlation between market development and enforcement of competition policy rules. That is not surprising: compe

Economists often talk about a strong correlation between market development and enforcement of competition policy rules. That is not surprising: competition policy aims at removing obstacles to economic activity, such as barriers to market entry, and it encourages new businesses to challenge incumbent players’ market power. Economic theory suggests that this dynamic brings about an increase in total production. It also suggests that the pressure from competition can trigger a ‘Darwinian selection’, so that firms are forced to be as efficient as possible if they want to survive in the market. This generally means lower production costs, higher quality and lower prices paid by consumers. Conversely, in specific circumstances, excessive competitive pressure may reduce incentives to invest (reducing profit expectations); and therefore, slow down the growth pace.

In more general terms, the increase in the complexity of the economy would require more regulation, in order to guarantee that companies compete on a level playing field and the optimal rewards for efficient investments are provided.

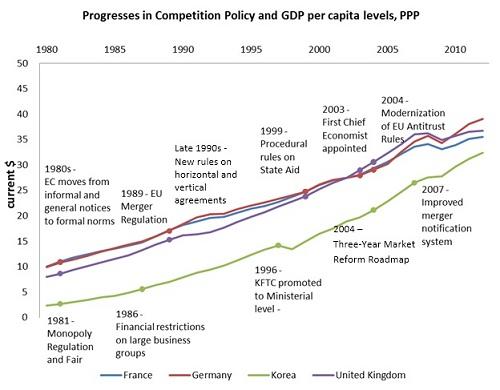

Data from the IMF World Economic Outlook – GDP per capita at PPP in current Dollars.

Figure 1 compares the evolution of the three main economies within the European Union: Germany, France and the United Kingdom, with South Korea’s economy in the 1980-2010 period. The graph shows that as market economies have developed and grown, competition policy rules have also evolved with merger control and antitrust enforcement being refined over time. For Europe, national competition laws and authorities were harmonised under European Union coordination. “Anti-monopoly” principles were originally set out in the Treaty of Rome of 1957 but the effective application of these rules only dates back to the 1980s[1]. In this period, competition policy mostly served to abolish barriers between member states and the creation of the single market. The European Commission replaced informal notices with formal norms and exemptions blocks lists. Subsequently, the major steps were the adoption of the Merger Regulation in 1989 (competences transferred to cthe Commission from national authorities and major attention shifting towards consumer welfare), new rules on horizontal and vertical agreements in the late 1990s (which permitted the most harmful ones to be focused on), the introduction of State Aid procedural rules in 1999, the first appointment of a Chief Economist in 2003 (meaning that economic analysis became crucial in assessing how mergers or cartels hamper competition in practice), and finally the Modernization of EU Antitrust Rules (aimed at reforming governance also with respect to national authorities).

In South Korea competition law and policy has progressed substantially in the past 30 years. The Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade ACT (MRFTA) were adopted in 1981, but were successfully enforced by the competition authority, the Korean Fair Trade Commission (KFTC), only after 1997. The Korean economy of the 1970s was dominated by public intervention, and competition was restricted as large business groups emerged. Shielding growing companies from competition might have proved successful, particularly when business was still in its infancy. However, the lack of competition was accompanied by a number of significant drawbacks, namely corruption, irregularities in market functioning and inefficiency of the internal organisation of large business groups.[2]

Corrections were later introduced. In 1986 restrictions on cross-shareholding between affiliates of the same group, ceilings on equity investments and restrictions on debt guarantees were imposed.[3] The 1990s were marked by increasing independence of the KFTC as the sole institution in charge of enforcing the MRFTA: in 1996 the KFTC became an agency at Ministerial level, but with limited governmental control. Particularly relevant in this period were improvements to competition-restricting regulations, the prohibition of anti-competitive mergers of any size, the introduction of a leniency programme and the new substantive test for dominant position and merger assessment based on market concentration. Competition law enforcement benefited from this legislative wave. In more recent times, the KFTC put in place the “Three-year Market Reform Roadmap” which included an increase in the upper limit for fines and a reward programme to encourage the reporting of violations. In 2009 the merger notification system was revised.

Competition law enforcement in the last 20 years – a graphical overview

Mergers and Acquisitions

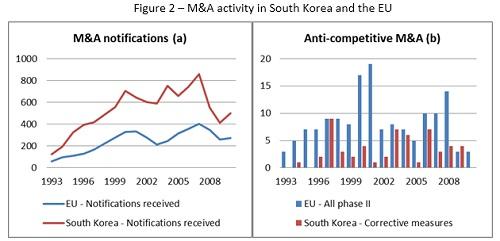

The below graphs compare EU and South Korea merger activity in the last 20 years.

Figure 2 – M&A activity in South Korea and the EU (Data for South Korea from Statistical Yearbook 2010 and several Annual Reports of the KFTC. Data for the EU from Statistics of the EC Competition.)

Panel (a) of Figure 2 shows that the number of annual M&A notifications to the respective authorities has been broadly increasing since 1993. The difference in the absolute number is explained by the fact that only mergers above the EU threshold (most importantly, the aggregate world-wide turnover of the undertakings concerned exceeding €5 billion) are notified to the European Commission (smaller mergers are dealt with at national level). The fall observed for notifications between 2007 and 2009 reflects the economic crisis in Europe and South Korea and a reduction in the total turnover of merged enterprises triggering the obligation to notify the KFTC in South Korea. Panel (b) compares the number of mergers for which a deeper investigation was deemed necessary to identify and possibly correct potential anti-competitive effects within the two jurisdictions. In the case of the EU, these are the ones that could not be cleared in phase I, and therefore include phase II, phase II with commitments and prohibitions; similarly, in the Korean jurisdiction, corrective measures are issued to rectify the proved anti-competitive effects and can imply divestments in favour of third parties or prohibitions.[4] During the period 1993-2000 in South Korea, out of 3200 notifications, 21 corrective measures were issued, while in the period 2001-2010 out of 6305 notifications, 35 corrective measures were issued.

South Korea merger law is substantially different to EU merger regulation. Within the EU, mergers are assessed through a balancing exercise: anti-competitive effects (such as incentives to increase prices) are compared to pro-competitive effects (such cost savings). If, ultimately, the net-effect on consumers is negative (that is: consumers should expect a welfare loss due to the merger) then the merger is blocked, unless effective remedies can be implemented. In South Korea, instead, efficiencies that do not accrue to the harmed consumers can be taken into account in the final assessment. Within the concept of “enhancing-efficiency effects”, the contribution to employment, regional economic development and stable supply of energy and other “nation-wide efficiencies” are taken into account. Also, the rise of a global competitor is taken into account when assessing a merger: “often large mergers may be efficient, especially if markets are international in scope” (OECD 2004).

Antitrust

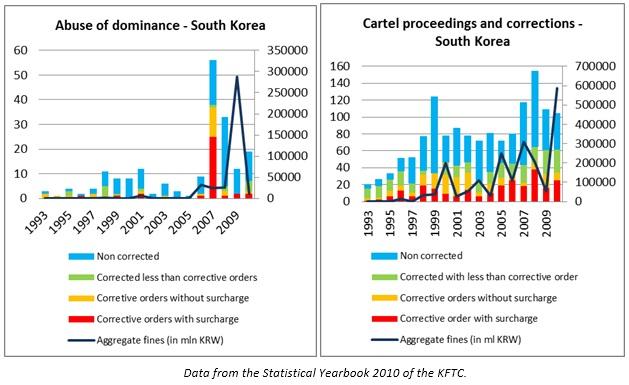

Data from the Statistical Yearbook 2010 of the KFTC.

Figure 3 show the pattern over time of antitrust enforcement in South Korea. In the left panel, the total number of investigations with respect to abuse of dominant position is shown by the vertical bars. The blue line displays the aggregate fines imposed by the KFTC for violations in this field. A breakdown of investigations into the types of correction imposed by the KFTC is shown by the different colours of the bars: a corrective order is issued when serious anti-competitive and harmful features are detected and can imply structural or behavioural remedies as well as surcharges, ie fines; other types of corrections include warnings, voluntary corrections and references to the prosecutor’s office (in Figure 3, they are labelled as corrected without corrective orders); all investigations leading to clearance with no commitment are labelled as non-corrected.

As can be seen, both the number of investigations and fines were low before the second half of the 2000s. The peak in investigations and number of fines observed in 2007 reflects the many cases of abuse of market dominance by multiple system operators. In 2009, the KFTC fined Qualcomm for KRW 273 bn (approximately EUR 154 ml at the time) for its conduct in the mobile communication market, which explains the spike in aggregate fines for that year.

The right panel shows the number of investigations and aggregate fines with respect to improper concerted acts, including cartels. As the figure shows, the KFTC has increased its enforcement activity in recent years. Substantial fines have been issued since 2000. An increasing number of cartel investigations have been carried out.

Under the Clean Market Project, in 2001 the KFTC started to target the possible emergence of cartels in the recently deregulated service sector[5] and it applied corrective measures in 33 industries by 2005[6]. More recently, in 2011 the KFTC successfully discovered a cartel of LCD screens manufacturers, including Samsung and LG, two of the largest business groups in Korea. In that case, the KFTC imposed a total fine of KRW 194 bn (approximately EUR 121 million, at the time)[7].

KFTC has had a good record on stopping harmful horizontal agreements (OECD, 2004): between the coming into force of the law in 1981 and 1997, the KFTC issued 74 corrective orders of which 30 were with surcharge; but from 1997 to 2010, it issued 386 corrective orders, of which 220 were with a surcharge (141 only from 2005).

Reference

OECD, 2004, “Korea – Updated report on competition law and institutions”.

[1] National authorities were already enforcing their own competition laws, with differences with respect to application.

[2] Annual Report 2011, Korean Fair Trade Commission.

[3] Since then, the regulation and oversight of large business enterprises are among the most significant functions performed by the KFTC, especially concerning their governance and ownership structures (OECD, 2004).

[4] In the statistics of the KFTC it is not possible to distinguish prohibitions from approvals with remedies.

[5] From OECD 2004.

[6] From Annual Report 2012.

[7] From the official press release.