The year of Ireland?

Ireland has assumed the role of the Presidency of the Council of European Union for the first half of 2013, which will likely attract more a

Ireland has assumed the role of the Presidency of the Council of European Union for the first half of 2013, which will likely attract more attention to the country. Yet the major question of the year is if Ireland will be able to return fully to market funding when the current official financial assistance programme expires at the end of this year.

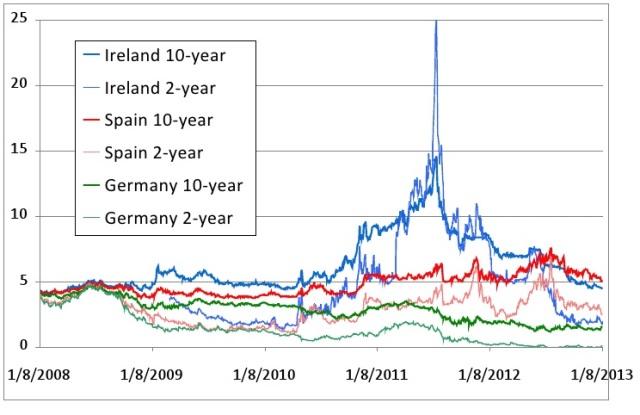

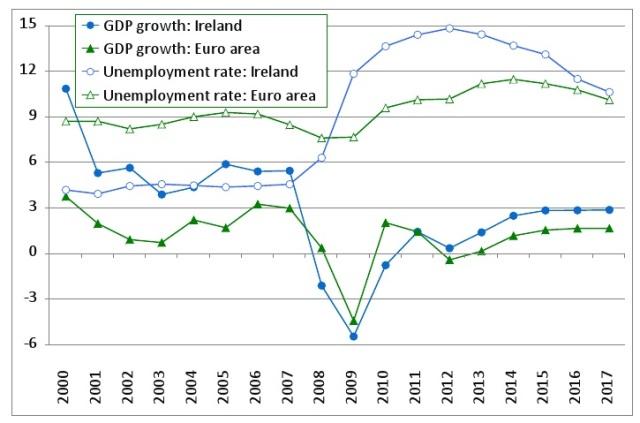

There are some encouraging signs. Secondary markets yields have fallen significantly (Figure 1). The Irish government could already return to market borrowing in July 2011 and yesterday there was a very successful syndicated bond issuance at a 3.3 percent yield, largely purchased by foreign investors. Since autumn 2011 deposits are returning to banks. There was a sizeable injection of private capital into the Bank of Ireland. Also, growth outlook is much brighter than in the rest of the euro area (Figure 2).

In my view the possibility of a full return to market funding will depend on two crucial issues: growth and a new deal on the promissory notes, ie notes that the Irish government issued to cover the losses of the Anglo Irish Bank and some other banks.

First, growth will be crucial to convince investors that the country can return to solvency and hence the adequacy of current forecasts needs to been seen. And while the total economy growth has resumed (a rare development among hard-hit countries), there is an uneven development across sectors. A few sectors dominated by large multinationals, such as the pharmaceutical industry, are thriving, but most of the other sectors have not yet recovered, as I studied in paper published last June. Also, the unemployment rate is forecast to diminish very slowly (Figure 2), prolonging the social pain.

Second, payments for the promissory notes will induce a huge burden for the Irish government in the coming years (see an excellent account of this debate in a recent paper by Karl Whelan). It is clear that other euro-area countries have benefited from the Irish socialisation of a large share of bank losses, which has significantly contributed to the explosion of Irish public debt. This calls for a banking union, as I argued in late 2011, and it is also in the best interest of European partners to make the Irish case a success story, by considering equitable measures. Indeed, the 29 June 2012 Eurogroup meeting has not just called for a banking union to break the vicious circle between banks and sovereigns, but also concluded that “The Eurogroup will examine the situation of the Irish financial sector with the view of further improving the sustainability of the well-performing adjustment programme.” It is time to deliver on this commitment.

Figure 1: Government bond yields, 8 January 2008 – 8 January 2013

Source: Datastream

Figure 2: Real GDP growth and the unemployment rate, 2000-2017

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook October 2012