Chart of the week: a deadly embrace

Europe is determined to break the vicious circle between sovereigns and banks. To achieve this aim, it appears to be clear that Europe will need a strong central supervisor, a common resolution authority as well as the appropriate fiscal backstop to help in case of major crisis when the resources of the resolution fund are exhausted. As Europe is advancing its work on the banking union, the increased dependence of banks on their sovereigns in the last year has not received sufficient attention.

An important reason for the link between banks and sovereigns is the fact that banks are holding government bonds on their books. Already before the crisis, European banks were holding large amounts of sovereign debt on their books. Total sovereign bond holdings amounted to around 1200 billion euro at the end of 2007 for all banks in the euro area. This made the resolution of the crisis so difficult. Any doubt about the solvency of governments translated into doubt of the banking system.

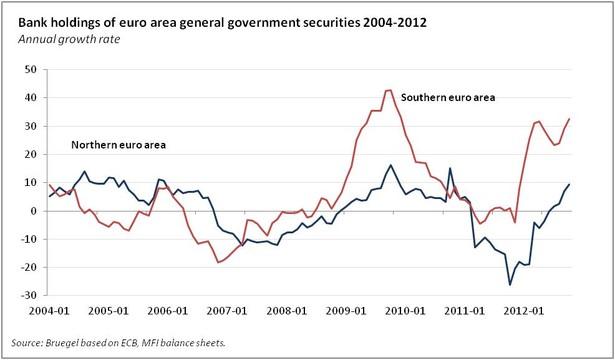

The deadly embrace between banks and sovereigns has accelerated at a rapid pace since then. Euro area banks are now holding more than 1600 billion euro of government securities on their books. Even more worrying than the absolute numbers is the increase of government debt on the books of banks located in Southern Europe. While banks in the north of Europe have increased sovereign bond holdings by only 5% since the end of 2007, banks in the South of Europe have doubled their bond holding. Banks located in Greece, Spain, Italy, Portugal and Ireland now hold more than 700 billion of sovereign debt on their books while in 2007 it was around 350 billion. In Spain, the number almost tripled. The government bond holdings of Italian, Portuguese and Spanish banks have in particular increased, by €180 billion, €30 billion and €160 billion respectively. Banks started financing governments in the 2009 when large deficits emerged in the South of Europe. During 2012, cheap ECB liquidity permitted banks in the South to buy government bonds yielding a handsome margin. The graph is showing the dramatic increase in bond holdings in the course of this year.

What does this deadly embrace mean for Europe’s banking union? The Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann has drawn his conclusion and asked for the introduction of risk weights to sovereign debt. That would require banks to hold significantly more capital for sovereign debt of Southern European countries. This proposal in principle makes sense. To break the link between banks and sovereigns would ideally mean a banking system with little sovereign debt on its books. However, the problem with this proposal is that it comes 5 years too late. Introducing such risk weights now would increase the cost of sovereign debt in the South of Europe significantly. This in turn would increase the likelihood of sovereign debt restructuring. Unfortunately, the deadly embrace has increased so much in particular in the last yeat that a sovereign debt restructuring would have incalculable consequences for the euro area financial system. If at all, such a proposal could only be implemented in a couple of years when doubts about solvency have already been overcome.

In the meantime, it however appears that sovereign debt restructuring is actually becoming less likely and more mutulisation is possible. Even if sovereign debt was unsustainable now, a debt restructuring would have more negative and incalculable consequences on the banking system now than 5 years ago. Even a strong bank restructuring regime would not be able to impose losses of a sovereign insolvency on bank creditors on such a scale. There would have to be support coming from the fiscal backstop to the resolution fund. In a sense, Europe will have the choice of rescuing its governments or rescuing its banks. The deadly embrace may therefore push Europe towards more mutualisation of risk now. Only in the long-run, a system with less mutualisation and less government debt in the banking system remains still possible.