Blogs review: an update on the fiscal cliff

What’s at stake: On January 1, unless preventive legislation is enacted, the U.S. economy will be gripped by a fiscal contraction equal to around 4% o

What’s at stake: On January 1, unless preventive legislation is enacted, the U.S. economy will be gripped by a fiscal contraction equal to around 4% of GDP. The lead negotiators for the White House and Congressional Republicans used the Sunday morning news to introduce their opening bids and defend their positions. Beyond the back and forth political process, the ongoing discussion poses the question of the optimal timing for fiscal contraction in a recovering economy.

What’s in it?

The Wonkblog has a useful FAQ about the fiscal cliff that details the measures to be implemented if Republicans and Democrats do not come to an agreement before the end of the month.

Five tax measures have provisions expiring at year’s end: the 2001/2003 Bush tax cuts; some of the 2009 stimulus measures (for example the Earned Income Tax Credit and the child credit); the Payroll tax holiday – which was included in the December 2010 tax deal and slashed the payroll tax rate on employees from 6.2 percent to 4.2 percent; the Alternative Minimum Tax – intended as a baseline tax for high earners; and the Extenders – a catch-all term tax wonks use for corporate tax breaks that need to be extended regularly.

Four types of spending cuts take effect next year: the sequester – mandated by the 2011 debt ceiling compromise that institutes a 2 percent cut in physician and other providers’ Medicare payments, and a 7.6 to 9.6 percent across the board cut in all discretionary spending; Budget caps; Doc fix – that would cut Medicare physicians’ payments; and Unemployment insurance.

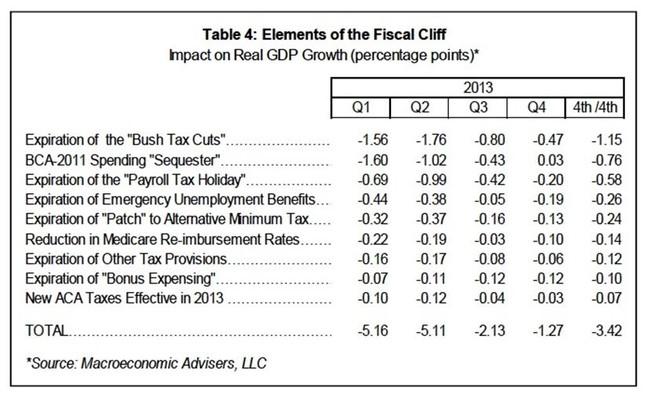

Macroeconomic Advisers breaks down how much each part of the fiscal cliff will take away from 2013 growth in the following table.

Source: Macroadvisers

The White House proposal

Ezra Klein summarizes the Democrat’s opening bid. First, to secure roughly $1 trillion in revenue from the expiration of the high-end Bush tax cuts. After that’s done, the White House is proposing another $600 billion in spending cuts and another $600 billion in tax increases. Add in the $1 trillion or so in expected savings from ending the wars, and you’ve got about $4.2 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years. Add in the savings on expected interest payments and you’re at almost $5 trillion. Subtract the White House’s stimulus request, and you’re somewhere a bit north of $4.5 trillion. Suzy Khimm has more details.

The proposal, loaded with Democratic priorities and short on detailed spending cuts, met strong Republican resistance, reports Jonathan Weisman in The New York Times.

Daniel Foster details what might be the most viable going option for the GOP: the Corker’s plan. It’s probably more accurate to say Corker’s plan is Romney’s plan made flesh with more plausible math and greater respect for political constraints. Most critically, it meets the Democrats’ sine qua non of concentrating tax hikes on wealthier taxpayers. But it does so while making the Bush tax rates a permanent feature of the tax code, instead of the ever-expiring creatures of “reconciliation” gimmickry they currently are. Corker’s approach has another, perhaps decisive, advantage: It exists. Corker’s got a bill in hand: 242 pages of “legislative language”.

A proposal to end debt-ceiling crisis forevermore

Ezra Klein writes that the idea comes from a most unlikely source: Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R), who proposed in July 2011 to permit the president to unilaterally raise the debt ceiling unless Congress affirmatively voted to stop him. There are differences between Obama’s plan and McConnell’s initial proposal. But the underlying mechanism remains the same: Congress can disapprove of the president’s decision to raise the debt ceiling, but unless they can overturn his veto, they can’t stop him. Measured by its cost-effectiveness, it’s perhaps the best idea in American politics today. The debt ceiling is an anachronism. It’s an accountability mechanism from the days when Congress didn’t much involve itself in federal budgeting. Today, Congress exerts full control over the federal budget. The debt ceiling isn’t imposing accountability on the executive but calling into question whether Congress will pay the bills it has already chosen to incur.

At 2.7% YoY growth, isn’t it a good time to introduce fiscal contraction?

Tyler Cowen sparkled a conversation about the timing of fiscal contraction with the following tweet: If we won’t face up to “the cliff” at 2.7% GDP growth, when again are we hoping to face it? Ryan Avent writes that that almost seems reasonable, doesn't it? But let's think about this for a second. First, the 2.7% growth rate is less encouraging than one might initially expect. Inventory adjustments accounted for a healthy chunk of third quarter growth (and nearly all of the upward revision from 2.0% at the advance estimate to 2.7% at the second).

Brad DeLong writes that Tyler Cowen is a quarter late: with a 2012:IV GDP growth rate now forecast at 1% per year, alarm bells ought to be ringing everywhere: more economic stimulus to boost demand is necessary – via monetary policy, via financial policy (especially housing finance), and via fiscal policy. The fuss over the "fiscal cliff" is crowding this out.

Paul Krugman writes that the time for austerity is when the economy is close enough to full employment that the Fed is starting to raise rates to head off an undesirably high rate of inflation; at this point, given the case for somewhat higher inflation, I’d say that we shouldn’t even think about this until unemployment is well below 7 and falling fast.

The simple analytics of invisible bond vigilantes

Suzy Khimm writes about the contrast between what financial industry honchos say worries them and what financial markets seem to be saying. Paul Krugman writes that what Khimm doesn’t note, however, is that the problem with bond vigilante scare tactics runs even deeper than that — because it’s actually quite hard to tell a story in which a loss of confidence in U.S. bonds hurts the real economy.

Paul Krugman writes that a simple Mundell-Fleming model (M-F is basically IS-LM applied to the open economy) to illustrate his point. An attack by bond vigilantes has very different effects on a country with a fixed exchange rate (or a shared currency) versus a country with a floating exchange rate. In the latter case, in fact, loss of confidence is expansionary. Think about it this way: with the Fed setting interest rates, any loss of confidence in U.S. bonds would cause not a rise in rates but a fall in the dollar – and a fall in the dollar would be a good thing, helping make US industry more competitive.