Chart of the week: euro-area imbalances before and after the crisis

The recent publication by the European Commission on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances outlined that the challenge of divergence and rebalancing between euro area countries remains. Our chart of the week illustrates this in a striking way: 5 years after the start of the crisis, internal imbalances haven’t narrowed. They have increased.

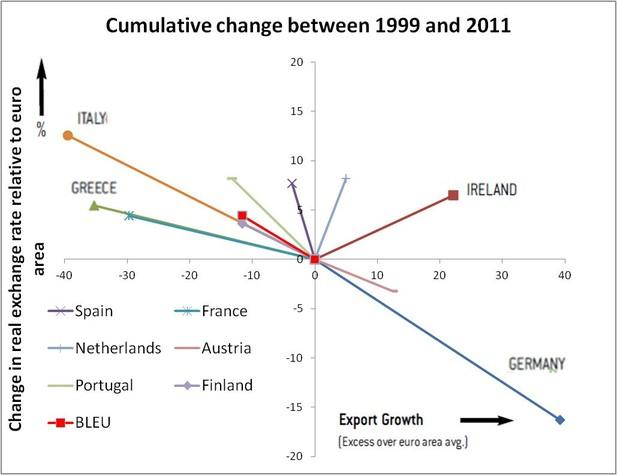

Our first chart – which covers the pre-crisis period – was first published in a 2006 paper by Alan Ahearn and Jean Pisani-Ferry and was subsequently picked-up by Dani Rodrik and the BBC to illustrate that the convergence assumption of the EMU architects was fundamentally flawed and that internal imbalances were at the core of the euro crisis.

This chart plots on the horizontal axis each country’s export performance, and on the vertical axis each country’s change in real exchange rate for the pre-crisis period since the launch of the euro. Both indicators are expressed in relative terms; that is, they display the difference between the country in question and the euro area as a whole.

Note: BLEU stands for Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union. The REER – real effective exchange rate – is based on unit labor cost measurement. Source: AMECO (Exports), Eurostat (REER).

From 1999 to 2006, relative price changes were a strong predictor of the behavior in exports: countries experiencing a relative appreciation (depreciation) of their real exchange rate experienced a relative decline (increase) in their exports. Ireland was a special case as it experienced both an appreciation and an export boom. In the words of Dani Rodrik “that is what is called an "equilibrium real appreciation": the real exchange rate movement is the result of export performance, not the other way around.” In Spain, the loss in exports was largely comparable to the rise in prices suggesting that outside of price developments, Spain didn’t see its competitiveness decline as worryingly as the current narrative on the crisis suggests. On the other hand, countries like Greece, France and Italy suffered very large decline in export with smaller increases of their domestic prices suggesting that something more profound was happening to their economies that a simple decline in price competitiveness. But, as pointed out several times by Antonio Fatás, these differences pale in comparison with the divergence between that group of countries as a whole and Germany, which – through a process of increased productivity with limited wage growth – have managed to reduce its relative unit labor cost and increase its exports.

Our second chart expanding the sample to 2011 allows capturing the effects of the crisis on these developments. The striking part is that imbalances have – if anything – increased during the crisis. There have been some improvements as in the case of Spain. The "equilibrium real appreciation" of Ireland, which certainly overshoot ahead of the crisis, appears now closer to fundamentals. Meanwhile, however, Germany, Italy, Greece and France have continued to diverge further.

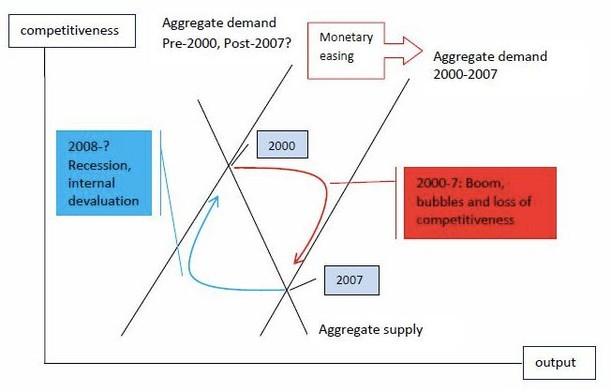

Simon Wren-Lewis (HT Kantoos) provides a nice framework to discuss the developments we have outlined in the form of a Swan diagram (see below). For the countries in the periphery, the pre-crisis period corresponds to a rightward in the AD curve, translating into a higher output level and a real appreciation. The post-crisis period corresponds to a leftward shift in the AD curve, which will eventually translate into a reduction in output and competitiveness gains. But because of adjustment lags, the economy moves along the blue arrow rather than jumps straight to the new equilibrium point.

Our data shows that the downward trend in competitiveness for peripheral countries has indeed stopped but has not yet been reversed despite several years of negative output gaps. Quite worryingly, the divergence in export patterns has, on the other hand, continued.