Corporate balance sheet adjustment: new stylized facts and its relevance for the euro area

We analyse corporate balance sheet adjustment episodes in Germany and Japan as well as a sample of 30 countries using national account data. Corporate

We analyse corporate balance sheet adjustment episodes in Germany and Japan as well as a sample of 30 countries using national account data. Corporate balance sheet adjustment tends to be long lasting and associated with strong effects on current accounts, investment and wages. Adjustment episodes lead to significant changes in corporate balance sheets ratios with a built-up of liquidity and a reduction of leverage. The adjustment is generally achieved by reducing investment and increasing savings on the back of a falling wage share. A better understanding of corporate balance sheet adjustment processes is critical for understanding macroeconomic divergence within EMU.

Deep economic crises are associated with stress in public and private sector balance sheets and they are often followed by protracted periods of balance sheet adjustment. However, while economists have recently spent much time assessing sovereign debt and the financial health of banks, balance sheets of non-financial corporations have been subject to less scrutiny. Our recent paper analyses the causes and macroeconomic consequences of balance sheet adjustment processes in the non-financial corporate sector.[1]

Corporate balance sheet adjustment has been an important driver of current account surpluses in some euro-area Member States, in particular Germany, over the past decade. Increasing corporate borrowing, in turn, has been to different extents driving large current account deficits in a number of South European countries. Understanding the determinants of corporate balance sheet adjustment is therefore critical for a better understanding of the factors driving current account divergences within the euro area. Such balance sheet adjustment does not only operate via increased or reduced corporate investment. One of our main new findings is the income channel of balance sheet adjustment on domestic demand: corporate savings are adjusted on the back of changing wage payments.

In the euro area, non financial corporations adjusted their balance sheets by significantly following the downturn of the early 2000s and the global economic crisis has also left a strong footprint on euro-area corporate net lending (NLB)[2]. Similar cyclical developments can be observed in the US where corporate net lending has remained firmly in positive territory since the global financial crisis (see figure).

Figure 1. Net lending/borrowing of non-financial corporations, Eurozone and US (1999Q1 to 2011Q2; in % of GDP)

Sources: Commission services, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Two important episodes of balance sheet adjustment in the recent history namely Japan in the 1990s and Germany in the early 2000s show the significance of adjustment both in terms of persistence and size. Graph 1 shows that the adjustments in these two countries took at least a decade and that changes in net financing needs of the corporate sector were significant also in macroeconomic terms. In Germany, the large increase in corporate net lending during the period 2001-2007 corresponds to exactly the period of significant increase of the current account surplus.

Figure 2. Corporate net lending/borrowing (% of GDP)

Sources: Cabinet office Japan and Eurostat sectoral accounts.

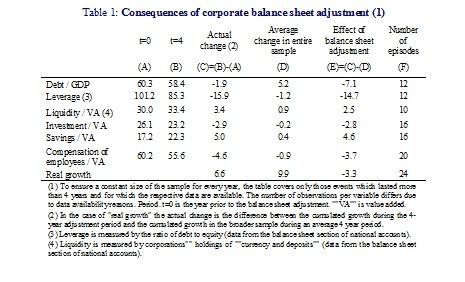

To get a better understanding of the pattern of typical balance sheet adjustment episodes, we analyze a sample of 30 countries. We identify episodes balance sheet consolidation as periods of large and persistent increases in non-financial corporations’ net lending (NLB). We then calculate changes in key macroeconomic variables such as corporate balance sheets, growth and wages during these episodes. The main results are presented in Table 1.

A number of interesting stylised facts on corporate balance sheet adjustment processes can be derived from the table.

(1) The Debt to GDP ratios are significantly reduced, in particular when compared to the overall sample, in which debt tends to follow an upward trend. Similarly, corporate leverage (i.e. the ratio of debt to equity) is reduced significantly, by almost 16 pp of corporate value added.

(2) Corporate balance sheet adjustments are associated with significant increases in the holdings of liquid funds. The increase in the sample averages 3.4 pp of corporate value added.

(3) Compensation of employees as a share of corporate value added falls by almost 5 pp.

(4) At the same time, corporate savings in percent of corporate value added increases substantially by 5 pp. The increase in savings thus corresponds very much to the decrease in labour compensation.

(5) Investment in percent of corporate value added equally falls substantially by around 3 pp of corporate value added.

The evidence presented thus shows that corporate balance sheet adjustments have very large and significant effects on wages, investment, savings, current accounts and corporate balance sheets themselves.

The paper also analyses the drivers of corporate balance sheet adjustment. With a panel econometric exercise, we find that balance sheet adjustment processes are triggered by macroeconomic growth downturns as well as high debt, low liquidity of the corporate sector and falling stock markets.

A number of important policy conclusions emerge from the analysis.

(1) Given the macroeconomic cost of adjustment, prevention of excess leverage in the corporate sector is important. Surveillance of corporate leverage should be a key element of the new macroeconomic imbalance procedure recently adopted by the EU institutions in the context of the so-called 6-pack.

(2) In the current context of persistently depressed growth prospects, risks of large balance sheet adjustment are maximised. A clear growth strategy is needed in order to avoid a vicious feedback loop where negative growth feeds balance sheet adjustment which in turn lowers growth.

(3) Micro economic measures should also be considered to ease the adjustment process. Better access to capital markets can reduce the need to resort to internal funds for adjustment. As shown by the Japanese experience, default of truly insolvent corporations may be preferable to speed up the resolution of the debt overhang.

(4) Last but not least, fiscal policy can play a role in smoothing the negative growth effects of corporate balance sheet adjustment. Given that most euro-area Member States with high corporate leverage have no room for fiscal manoeuvre, an appropriate aggregate fiscal stance at the euro-area level might require a slower pace of consolidation in the Member States where such a room for manoeuvre exists.

A version of this column was also published by Vox.EU.

[1] Ruscher, E. and G. Wolff (2012), "Corporate balance sheet adjustment: stylised facts, causes and consequences", published as European Economy, Economic Paper No. (February) and Bruegel Working Paper 2012/3 (February).

[2] Balance-sheet adjustment can be captured at a macroeconomic level by changes in corporate net lending or borrowing (NLB). Corporate NLB measures corporations’ net needs in terms of external finance. A large reduction in the demand for external finance leads to an adjustment of balance sheets.