Chart of the week: historical perspectives on France’s great recession

We are following a few of important posts comparing our fate in this Great Recession (or lesser Depression as Brad DeLong likes to call it) to earlier

We are following a few of important posts comparing our fate in this Great Recession (or lesser Depression as Brad DeLong likes to call it) to earlier crises (see for example Eichengreen and O’Rourke for the world economy, Jonathan Portes for the UK, Calculated Risk for the US, and Paul Krugman on Europe). We compare the path of the French economy after 3 major shocks, which are usually considered as the cause (or at least the trigger) of global crises.

We focus on:

- the October 29 stock market crisis;

- the October 1973 oil crisis;

- the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008.

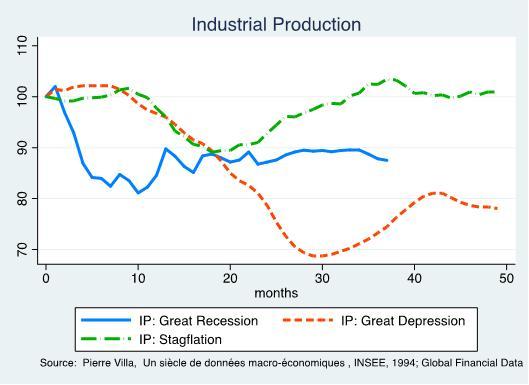

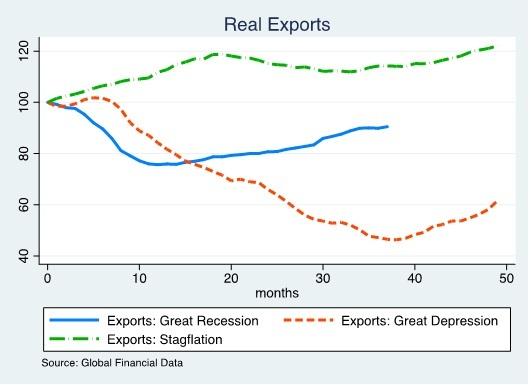

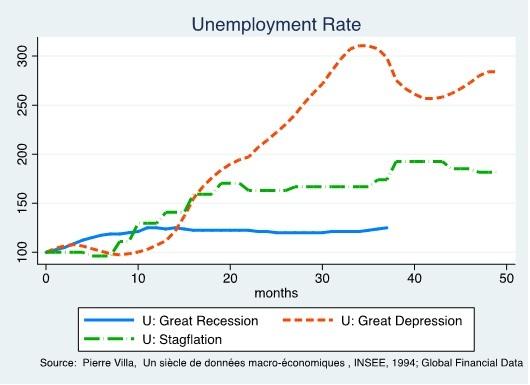

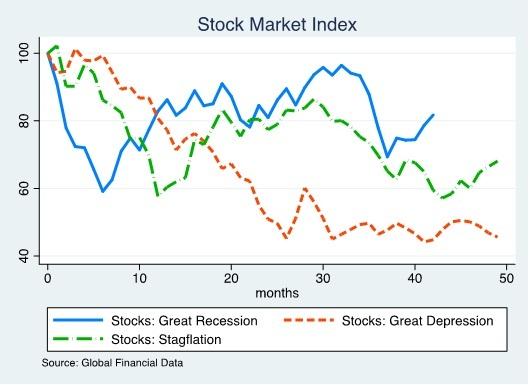

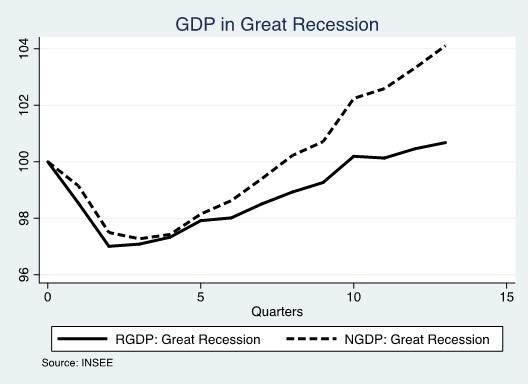

For each recession, we set the value of the series equal to 100 at the month of the shock.

The October 1973 shock was not primarily a financial crisis (although the stock market fell sharply) but led to a very severe economic downturn, which put an end to the strong post-war growth period. While production went back to the trend after 3 years, the inflation and unemployment crisis lasted until the 1980s. The Great Depression is interesting for its depth and timing as the dynamic of the French economy was somewhat different than that of the rest of the world: the depression was initially milder, but lasted much longer partly because France did not leave the Gold standard until 1936 (see Pierre-Cyrille Hautcoeur for more on Great Depression in France).

There are a couple of interesting facts to note from the diagrams below:

1. The initial shock :The shocks to the stock market, industrial production and exports were stronger in this Great Recession than in the two previous shocks. This is despite the fact that France was not particularly hit harder than other countries in the initial phase of the Great Recession. To a certain extent, the relative strength of this initial shock compared to that of the Great Depression reflects the fact that France entered the Great Depression later than other countries. An undervalued Franc initially insulated the French economy from the deteriorating international situation until England left the gold standard in September 1931. In addition, expansionary fiscal policy helped the French economy in 1930. In many countries in Europe, the failure of the Credit-Anstalt (an Austrian bank) in May 1931 was the true starting point of the depression. Exports and unemployment started to be affected 10 months after the initial Wall-Street shock. If we had taken the bust of the US housing bubble in the summer 2007 as the starting point of the current crisis, we would not observe an immediate negative shock in Europe. Contrary to 1929 , the Lehman bankruptcy created an immediate international contagion. But as in the 1930s, the current European crisis has been amplified by subsequent banking and political troubles that occurred more than a year after the initial stock market crash.

2. Magnitude of the shock: It is clear that, at the moment, that a second great depression has been avoided. It is about 20 months after the shock (which corresponds to the 1931 crisis for the Great Depression) that the series start to diverge. The 1970s and 2010s economies start to recover while the 1930s keeps falling. The jump in the unemployment rate today seems far smaller than the precedent crises but remember that the level of French unemployment was around twice as large as in 1973 and that unemployment data for the interwar in France are notoriously bad, at least in levels (See Robert Salais for example). In many ways, the current crisis looks now closer to the 1973s crisis but without inflation and with a slower recovery of production. The figure of the price indices is especially striking. Price level in 2010 is stagnating: so both an inflation crisis and a deflation crisis seem to have been avoided. In a sense, central bankers have avoided a repeat of the past, but have managed to make their own mistakes by keeping the economy stuck in a stagnating trap.

3. Recovery: The recovery from the Great Recession has been slow, as industrial production and unemployment still haven’t reached their pre-Lehman levels. The recovery in industrial production and exports appears weaker in France than in the rest of the world and in Europe when compared with the figures of Eichengreen and O’Rourke and Krugman. Similar to during the Great Depression, France seems to recover at a slower pace than the rest of the world as industrial production and unemployment are neither falling nor coming back to trend, which is reminiscent of the unemployment situation of the late 1970s. Interestingly, IP has not yet reached its pre crisis level while GDP has. In other words, firms and households have started again to invest and consume but the production is not there yet something that fits both the external accounts picture and with the rapid loss of industrial capacity in France.