The euro conundrum

In this piece, Zsolt Darvas talks about how the markets are charging high interest rates for sovereign bonds of peripheral eurozone countries, while keeping the euro exchange rate strong, at the same time. The euro-dollar exchange rate continues to stay well above its equilibrium value and its depreciation earlier this year meant just a correction toward equilibrium. Is there not an anomaly? And do recent eurozone governance proposals play a role? What is the path forward?

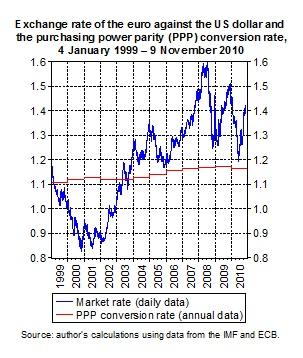

Markets are charging high interest rates for sovereign bonds of peripheral eurozone countries, but are at the same time keeping the euro exchange rate strong. Indeed, the euro-dollar exchange rate continues to stay well above its equilibrium value as defined by purchasing power parity since mid-2003, and its depreciation earlier this year, which frequently occupied press headlines, meant just a correction toward equilibrium (see Figure). Is there not an anomaly? And do recent eurozone governance proposals play a role?

The strength of the euro suggests that markets do not expect a disorderly dissolution of the euro project, but large sovereign bonds spreads suggests that a government default (or debt restructuring) is not unthinkable. Recent worries about possible defaults have been amplified by the debate on a possible EU sovereign debt restructuring mechanism, following the Merkel/Sarkozy agreement in Deauville on 18 October 2010 and the conclusions of the European Council of 28-29 October. Such a mechanism would facilitate any orderly defaults by governments in a similar way to existing bankruptcy rules for corporations.

This proposal makes sense, but was missing from the recent eurozone governance reform proposals of the European Commission and of the Task Force headed by European Council President Herman Van Rompuy, which placed major emphasis on strengthening existing rules and imposing sanctions.

Sanctions do not offer an appropriate solution to current eurozone fiscal worries. They would not have helped much in averting the current crisis except perhaps in Greece and Hungary, because the major reason why 24 EU countries are currently under the EU’s excessive deficit procedure was private sector imbalances and weaknesses of the European banking industry. Sanctioning at a time of a crisis or when countries are struggling to get out of the fiscal mess caused by the crisis does not make much sense.

Also, sanctions will result from decisions of the European Commission and the European Council and there will be fruitless debates and unsettling disputes, which would not help much to foster the European project further. Sanctions can easily carry the political message that ‘Brussels fines us and does not understand our situation and social problems’. This may give rise to anti-EU sentiment, which would clearly be undesirable. It would be much better to design institutions that encourage discipline through market forces.

The sovereign default mechanism could be such an institution, but there is an even better solution: the introduction of a common Eurobond covering up to, say, 60 percent of member states’ GDP (‘Blue bond’) with the joint guarantee of all participating countries. Countries would issue any additional bonds with their own guarantee (‘Red bond’), which would be junior to the Blue bond, and the orderly sovereign default mechanism should be put in place for the red bonds only. Thereby, this system would provide an extremely strong incentive for countries to convince markets that their red debt is safe, thus promoting fiscal discipline.

Unfortunately, there is little hope that the common Eurobond will be introduced. Instead, the Commission/Task Force proposals will probably be adopted. These also include a number of good initiatives, such as the new ‘excessive imbalance procedure’, which may help to design remedies for private sector vulnerabilities, and the requirement to improve national fiscal frameworks. There is an increasing chance of agreement on a European sovereign debt restructuring mechanism.

Are these reform proposals causing the seeming anomaly between the pricing of the euro and the pricing of peripheral eurozone bonds? The possibility of a restructuring mechanism has likely contributed to rising interest rates, even though the mechanism should apply only to bonds issued after its introduction. But openly discussing the possibility of future sovereign defaults has given rise to the current worries. And Greece indeed has a real solvency problem: high debt, a high deficit, weak tax-collection capability, social unrest and a loss of confidence, and it is difficult to see how this country will be able to avoid default or debt restructuring should a new negative shock occur. But the cases of Ireland and Portugal are different and the best solution for them would be to turn to the EFSF (European Financial Stability Facility) and the IMF in order to buy time.

The continuing strength of the euro does not primarily originate in the recent quantitative easing of the Federal Reserve, nor in governance reforms. Markets have likely realised that earlier worries about the break-up of the eurozone were unjustified and may have also grasped the political commitment behind the euro. It is in Germany’s best economic interest as well to stay inside: a new D-Mark would appreciate excessively, thus halting the German recovery. And even if a eurozone sovereign were to default, it should not impact the existence of the euro. The most difficult challenge the eurozone will face is the joint fiscal and competitiveness adjustment of certain Mediterranean economies which will likely lead to significant growth divergences within the eurozone. But at least the fiscal adjustment is not mission impossible: several east Europeans gave examples of how to do this in the midst of much deeper recessions.

Zsolt Darvas is Research Fellow at Bruegel, Research Fellow at the Institute of Economics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Associate Professor at the Corvinus University of Budapest.