China’s overheating economy

What’s at stake: Figures published on January 21st confirmed that the Chinese economy was roaring ahead, growing by 10.7% in the fourth quarter of 2009 from a year earlier. Industrial production, retail sales, and bank credit all jumped by respectively 18.5%, 17.5%, and 32% in the year to December.

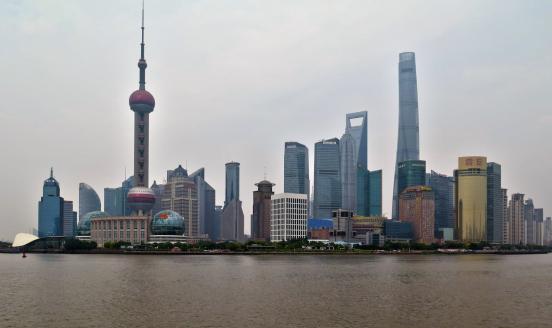

Barry Eichengreen writes that Chinese markets display all the symptoms of bubble trouble. Why is no mystery. By preventing the exchange rate from moving, China imports accommodative foreign monetary conditions. Zero interest rates may be appropriate for a still depressed United States and Europe, but they are not appropriate for a booming China that increasingly looks like an overheated China. So far Chinese officials have settled for half measures. They have encouraged lenders to tighten mortgage lending standards. They have imposed a 5.5 per cent sales tax on residential property held for less than 5 years. But this is like trying to hold back a flood with a finger. What China needs is substantially tighter monetary conditions to prevent its already blazing housing market from overheating further. And the only way of effectively tightening credit is by substantially appreciating the renminbi.

Anoop Singh of the IMF discusses the puzzle of Asia’s rapid rebound: how is it that Asia has rebounded sooner and more strongly than the rest of the globe from the economic slump when the region is so heavily dependent on exports for its growth? One part of the answer is the powerful measures the region took to counteract the crisis. Another part of the answer is that in this business cycle, international trade has fluctuated far more than the GDP of advanced countries. Global trade collapsed at the end of 2008 – so output in Asia’s export-oriented countries fell further than that of countries at the centre of the crisis. But since February, trade has been normalizing rapidly, tracing out a pronounced V-shape. Unsurprising then that Asia’s recovery is duplicating that V-shaped.

Yu Yongding writes that while expansionary policies have succeeded in ensuring a V-shape recession, their medium and long-term effects are worrisome. Monetary policy has in particular been far too loose. Unlike the US, China did not suffer from a liquidity shortage and a credit crunch during the global financial crisis. Thus, low interest rates and non-market interference, rather than demand from enterprises, fuelled explosive credit growth in the first half of 2009, surpassing the full-year target. If commercial banks had been allowed to base lending decisions solely on economic considerations, credit and money supply would have grown more slowly, limiting the risk of rising bad-loan ratios, stalled enterprise reform, inflationary pressure, and a resurgence of asset bubbles as excess liquidity enters equity and real-estate markets.

Michael Pettis writes that China’s response to the global crisis involved an unprecedented expansion in credit, which is likely to have exacerbated the country’s underlying imbalances. This means that within two or three years Chinese banks are going to be faced simultaneously with the double whammy of slowing economic growth and rising non-performing loans. This will put a damper on international risk-taking.

*Bruegel Economic Blogs Review is an information service that surveys external blogs. It does not survey Bruegel’s own publications, nor does it include comments by Bruegel authors.